The current financial crisis has an Achilles Heel: Who can we blame? No single person orchestrated, coordinated, and managed the financial disaster. Unless you believe the devil or the Illuminati were behind it, the financial disaster remains more of a systemic problem than one of twisted minds.

But there are key players involved. They are men of government, business, and, thanks to the revolving door, both at once. When they slip up, permanent damage results.

For the purposes of this list, financial crisis refers to the current crisis, characterized by subprime mortgage defaults, widespread bank failures, an unprecedented government bailout program, and a basic lack of trust in the economy. A man behind the crisis is someone in a position of power during the crisis who helped form, perpetuate, or aggravate it.

We listed 25 men behind the financial crisis below:

25. Christopher Cox

Former SEC Chairman Cox left a mixed legacy. On the one hand, Cox, who served until early 2009, increased transparency, enforcement, and investor communications in the financial industry. On the other hand, he missed red flags about Bernie Madoff. He didn’t see the severity of the Wall Street mess until it was too late. Cox generally has a good reputation, but he didn’t speak up soon enough, which allots him a space on this list.

24. Adam Applegarth

Applegarth ran Britain’s Northern Rock between 2001-2007. After the bank, one of the largest mortgage providers in the country, was bailed out by the Bank of England, Applegarth ran the other direction—with $1.15 million in hand. He now holds the dubious honor of heading the first bank in Britain that customers ever ran on.

23. Bernie Madoff

Madoff wasn’t directly involved in the corporate and regulatory mess that led up to the crisis, nor is he perpetuating it. But his $65 billion Ponzi scheme played an important role in aggravating a sense of cultural distrust in the financial sector.

Part of the economy’s woes come from a communal unwillingness to put money back into a deceitful economy. Madoff symbolizes this sense of reluctance, a reminder that trusting “experts” with your money is a bad idea.

22. Raymond MacDaniel

MacDaniel is the CEO of Moody’s Investor Services, one of the world’s biggest ratings companies. His company (along with Fitch and Standard & Poor’s) offered AAA ratings to subprime-backed securities during the housing bubble, which could be seen as an oversight.

But MacDaniels not only acknowledges that his agency has to manage an inherent conflict of interest–it is paid by some of the investment banks it rates–but blames Moody’s faulty ratings on bad information. His response to a Financial Times article uncovering a ratings model error was equally baffling. Moody’s paid him a $350,000 bonus this year for his troubles.

MacDaniel’s lax enforcement of the research and independent questioning his ratings agency should have done during the crisis, combined with his current defensive stance, makes him a man behind the crisis.

21. Chris Dodd

Senator Chris Dodd, chair of the Senate Banking Committee, is notoriously in cahoots with banks, which in part explains why Wall Street, not Main Street, gets the benefit of the bailout. In 2003, Countrywide Financial granted Dodd below-market mortgage rates on two of his homes as a result of his membership in the “Friends of Angelo” program. In 2008, Dodd proposed a bailout bill that included helping Countrywide. Coincidence? Hardly.

Dodd ranks first among senators for insurance industry contributions, including more than $20,000 from Countrywide (and those reduced rates) and nearly $134,000 from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Dodd refused to admit Fannie and Freddie were in trouble until late last year. Another notorious Dodd scandal (this article explains http://www.salon.com/opinion/greenwald/2009/03/17/dodd/ how Dodd may have actually been a pawn in this. Don’t worry, conservatives, it was Geithner and Summers who played him) concerns his flip-flopping over having retroactively added an executive pay limit onto the stimulus bill.

Sen. Dodd recently released his Countrywide financial statements after months of pressure—but did not allow the media or the public to see them.

20. Richard S. Fuld, Jr.

Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy spurred panic in the fall of 2008. Fuld, the 14-year chairman and CEO of Lehman, helped foster the bank’s collapse by refusing to sell it when he had the chance. Despite the ego blow, Fuld made off with almost $75 million in the two years leading up to the crisis (2006 and 2007), allotting him the dubious honor of winning the 2008 Financial Times’ Overpaid CEO Award of 2008.

19. Bill Clinton

The Glass-Steagall Act, had it been left intact, could have greatly reduced the severity of the current crisis. But the Clinton administration helped repeal the act, dealing a fatal blow to the economy. The clincher? Clinton doesn’t even regret it. “In the case of the current crisis,” he is quoted as saying in a meeting prior to this year’s Global Initiative Conference, “I believe the bill I signed allowed Bank of America to take over Merrill Lynch.” That’s some twisted logic.

18. Chuck Schumer

Schumer, like Chris Dodd, receives handsome contributions from financial institutions. He opposed regulating Fannie and Freddie in the years leading up to the crisis, but his real claim to fame was triggering the IndyMac bank run in June 2008. Schumer wrote in a letter to a regulator that he was “concerned that IndyMac’s financial deterioration poses significant risks to both taxpayers and borrowers and that the regulatory community may not be prepared to take measures that would help prevent the collapse of IndyMac.”

Shortly after Schumer’s remarks, depositors ran on the bank, withdrawing $1.3 billion in 11 days. Some critics say it led to the bank’s downfall; the truth is that it may have only accelerated it. Regardless, the statement caused a panic—and one of the more memorable events of the financial crisis.

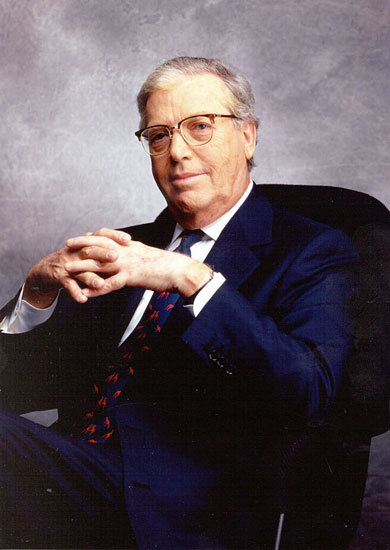

17. William Donaldson

Facing regulatory pressure from the EU, George W. Bush’s SEC Chief of Staff, William Donaldson, released banks from lending restrictions in 2004. In exchange, his team would be able to regulate them as bank holding companies.

Once the EU was appeased, Donaldson and his successor, Christopher Cox, slackened their regulatory power almost to the point of ignoring the banks entirely. According to Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi, during the last year and a half Cox was in charge, the SEC commission in charge of supervising the five major banks did no inspections—nor did it have a director.

BusinessWeek reports that Donaldson said “regulators had put in place formulas to properly monitor investment banks’ leverage.” Formulas aren’t of much use, though, if you don’t actually apply them to anything.

16. James Cayne

Bear Stearns wasn’t solely responsible for the financial crisis. Indeed, former CEO James Cayne acted like he didn’t see it coming. But it was the first big financial firm to fail, leading to a gut-wrenching domino effect. After Bear fell, confidence in the industry plummeted. JP Morgan Chase bought Bear with a government loan in March 2008. The rest is history.

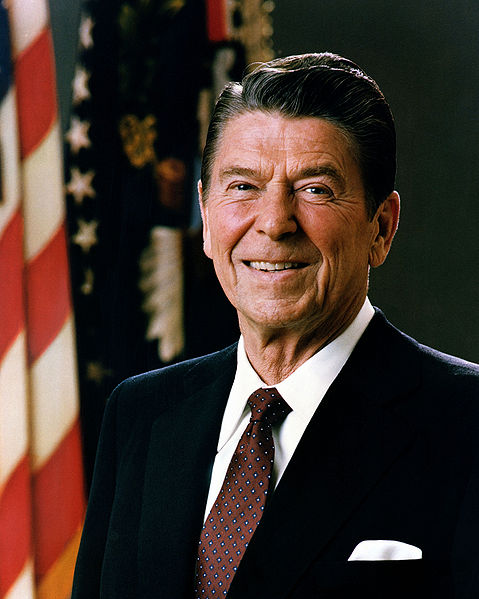

15. Ronald Reagan

Reagan oversaw the deregulation of the savings and loan industry. S&Ls traditionally used peoples’ savings to fund mortgages. The 1980 DIDMCA (Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act) enabled them to offer transaction accounts, consumer loans, and commercial loans. S&Ls started issuing credit cards and using up to 20% of their assets, as permitted by the new law, for consumer and commercial real estate loans.

A real estate boom and high interest rates encouraged S&Ls to pour money into risky financial ventures, including big real estate transactions, linked financing, and junk bonds. In 1986, the S&L industry collapsed, ironically resulting in more regulations.

Although the Reagan administration handled the S&L crisis well, the Teflon President seeded the risk-taking, Master of the Universe mentality that spawned the current crisis. Reagan turned deregulation into a dogma strong enough to blind businesspeoples’ ethics. This cultural legacy remains a pivotal factors behind today’s crisis.

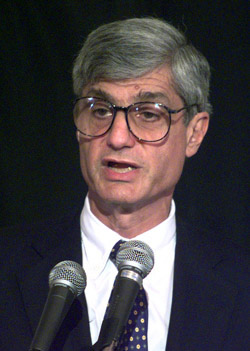

14. Robert Rubin

As Clinton’s Secretary of the Treasury, Rubin successfully opposed the regulation of derivatives. He also supported the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act. But his most famous stint is as an adviser to Citigroup, where he served as a director until this year.

Rubin encouraged the bank’s executives to increase trading in mortgage-backed securities and other exotic instruments, according to the New York Times. He also supported Citigroup’s “unwieldy financial supermarket model” during his tenure, says the Times. These stances, combined with a lack of internal oversight, contributed to Citi’s overexpansion and overexposure to risk. When the crisis hit, bloated Citi was slammed, leading to what amounted to a government takeover of the bank.

Rubin stepped down earlier this year amidst criticism from investors. Citi paid him $126 million over the past ten years.

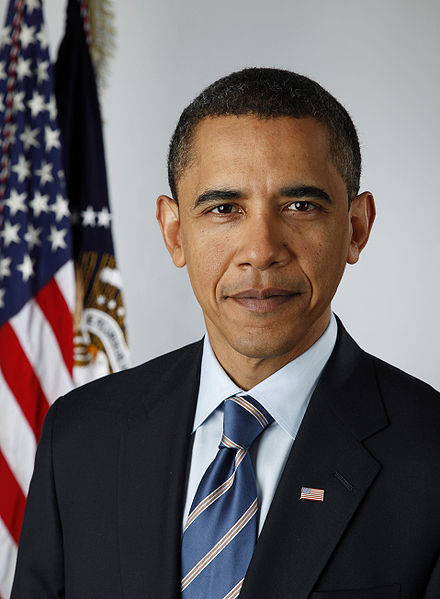

13. Barack Obama

In order to handle the financial crisis effectively, Barack Obama surrounded himself with people who have inside knowledge of the financial industry. The problem is that these people are also insiders. Stepping through the revolving door gave them a strategic advantage in helping out their industry. The result is that the economics branch of the government (run by Wall Street insiders) continues to bail out Wall Street.

Obama has the power to make the bailout process transparent, or have it changed entirely. He can appoint hearings, investigate the true scope of the country’s financial losses, and tell people the truth. But he chooses to sit back while the old guard—the people whose behavior caused the crisis—follows its own frenetic agenda.

If Obama wants to change the country, he needs to start from the inside of his own administration.

12. Tim Geithner

The man didn’t pay his taxes, was mentored by former Goldman Sachs CEO Robert Rubin (who helped block regulation of CDSs before the crisis), and continues on the bumbling, opaque vein that Hank Paulson initiated–yet nobody is asking for his head.

It’s business as usual for Geithner, who wants $2 trillion in taxpayer money to bail out fully capitalized and solvent banks. William K. Black, interviewed by Bill Moyers, points out the inconsistency: “Both statements can’t be true. It can’t be that (banks) need $2 trillion, because they have mass(ive) losses, and that they’re fine.” He also questions the logic behind sending $5 billion in taxpayer money to the Swiss bank UBS, then charging them $780 million in criminal fines. In essence, the government quietly bailed the same Swiss bank that was defrauding it by hoarding taxable income.

Black describes out two more Geithner missteps:

1. Geithner used to be the president of the New York Fed, which is supposed to regulate most of the country’s biggest bank holding companies. Yet Geithner has testified that he has “never been a regulator.”

2. There’s a Savings and Loan crisis-era law called the Prompt Corrective Action Law. This law mandates that when banks are insolvent and failing, regulators or the bank “must promptly correct the capital inadequacy.” If a bank does not promptly recapitalize, the law says that regulators must force it into receivership (further explanation is here).

Black claims that:

TARP II is designed to provide a federal subsidy to insolvent and failing banks. (It) violates the express purpose of the PCA law to resolve bank problems at the lowest cost to the FDIC and the taxpayers. Providing taxpayer “capital insurance” subsidies to insolvent or troubled banks increases the taxpayers’ costs.

So Geithner’s plan is not only wasteful—the government shouldn’t be paying off banks’ debts–but illegal.

11. Chuck Prince III

Businessweek reports that Citigroup, the second largest bank in the world, was “the biggest player in the roughly $400 billion SIV market (mostly CDOs).” Despite his company’s heavy investment in CDOs, Prince didn’t require his company to quantify its risk exposure. That means that Citi had no idea how risky its CDO investments were until they all collapsed.

When disaster struck, it hit Citigroup especially hard. The bank lost more than $20 billion in 2008. It cut 75,000 jobs. And the government gave it $54 billion in TARP funds, then guaranteed $306 billion in bad assets. Citi remains a mess for the government, taxpayers, and the financial industry.

10. Daniel Mudd

Franklin Raines’ successor as Fannie’s CEO, Daniel Mudd, tripled the entity’s purchase of potential subprime mortgages (those where buyers need to put down 10% or less) between 2005-2007, according to BusinessWeek. Mudd was under congressional and Wall Street pressure to boost Fannie’s position in capital markets. That meant extending more loans to low-income buyers, especially in overdeveloped markets like California.

When Mudd was forced to step down by the government conservatorship movement last September, Fannie had piles of Alt-A and subprime mortgages in its coffers. Mudd lost his severance, but earned more than $10 million during his tenure.

9. Larry Summers

Obama economic advisor Larry Summers has a history of shooting down regulation, taking money from financial firms, and bailing out companies with government funds.

When he worked in the Clinton administration, Summers, according to the American Prospect, advocated bailouts, lack of regulation, and asset bubbles. One notable example of his policies occurred when regulator Brooksley Born, then-head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) pushed a piece of derivatives regulation in the late 1990s. Summers was part of a trio that passed a law prohibiting the very kind of regulation Born was proposing. This particular type of CDS ended up bringing AIG to its knees.

Before gaining his current political appointment, Summers was informally lobbied by financial firms to the tune of $2.7 million, including $135,000 for a one-day speaking engagement at Goldman Sachs. That amounts to roughly $16,000 an hour. According to former regulator Bill Black (as interviewed by Bill Moyers), Summers’ engagement was the bank’s way of informally lobbying him before he gained his post in the new Obama administration. Summers also accepted perks like free rides on the Citigroup corporate jet.

In exchange, he continues to advocate on behalf of financial firms. The Wall Street Journal claims that Summers asked Chris Dodd to remove executive pay caps for Citigroup and other bailout recipients. He also helped bail out the very companies that paid him in advance.

8. Franklin Raines

Raines was Fannie Mae’s CEO and chairman from 1998 to 2005. Raines started a program in 1999 aimed at issuing Fannie loans to low-income individuals. The idea was to increase the number of low-income and minority homeowners (people with a lower probability of paying their loans back). He also loosened the credit requirements for the bank loans that Fannie purchased. Those actions, combined with Raines’ famous book-cooking, resulted in short-term gains for Fannie and Raines, but ended in disaster.

In 2004, Raines stepped down after an SEC investigation found “accounting irregularities” including shunting losses to C-level execs so that they could earn bigger bonuses. Officials later discovered that Raines had overstated as much as $6.3 billion in earnings.

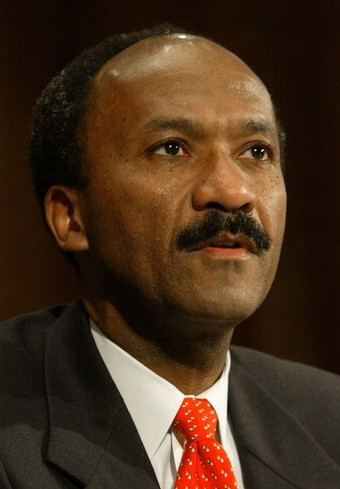

7. C.K. Lee and the Office of Thrift Supervision

The Office of Thrift Supervision—not the Fed or the SEC—was charged with regulating AIG, including its European operations, since 1999. The OTS, a small, relaxed operation that, through a legal loophole, regulated some corporate giants, only had one insurance specialist on its staff when it was regulating AIG, according to Rolling Stone. C.K. Lee, the regulator in charge of keeping AIG in check, later stated that because AIG said its CDSs were harmless, he believed them. Some regulation.

6. Angelo Mozilo

Remember how, in the not-too-distant past, mortgage brokers would try to convince you to take on ARMs, interest-only loans, anything but a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage? That kind of behavior had higher commissions, courtesy of Mozilo’s Countrywide, at its roots.

After co-founding Countrywide Financial, Mozilo built it into the biggest mortgage lender in the country. Countrywide investors enjoyed 23,000% returns between 1982-2002.

Mozilo himself made $479 million between 2001-6. He manipulated Countrywide’s stock price through private sales and buybacks, and spearheaded a “Friends of Angelo” program that offered Mozilo’s buddies, including a number of politicians, special treatment when it came to mortgages. Favors included below-market interest rates and reductions in mortgage payments.

Mozilo sold the company to Bank of America in October of 2008 at a fraction of its former stock price.

Mozilo may be out of the limelight, but his legacy continues. Old Countrywide execs like Stanford Kurland are now once again profiting off mortgages, albeit in a changed market.

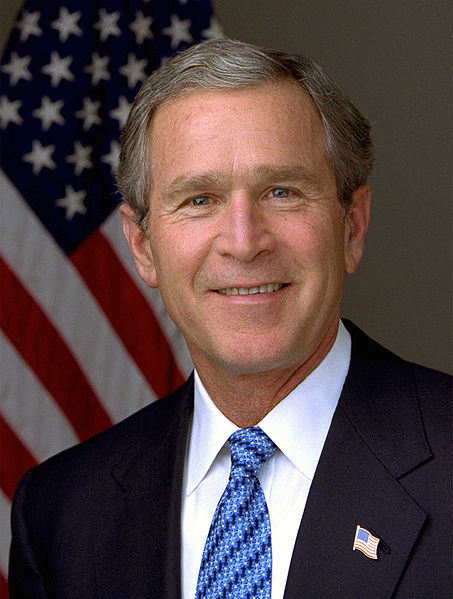

5. George W. Bush

The Bush administration didn’t meddle in the building regulatory and investment bank mess that catapulted the crisis. That, it turns out, was one of its biggest mistakes. That’s nearly a decade of no oversight. Add the $3 trillion sunk into the Iraq War, and you have a national budget disaster, courtesy of GW.

Rating agencies ignored loan files until after the collapse. Federal investigators ignored signs of fraud dating back as early as 2004. According to William K. Black, 500 white-collar FBI specialists were reassigned to research national terrorist issues. Years later, the Bush administration didn’t replace those 500 agents, who would have been able to research the banking meltdown before it hit. That’s one reason for the suddenness and severity of the crisis.

4. Phil Gramm

Senators Phil Gramm and Jim Leach sponsored the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, a Depression-era bill that prevented commercial banks from acting as investment banks. The bill also stopped banks from entering the insurance business.

Gramm’s repeal of Glass-Steagall helped spawn bloated financial conglomerates like AIG and Citigroup. The investment-cum-commercial practice of writing loans, then selling them off became standard procedure.

A year later, Gramm wrote a law that prevented CDSs from being regulated as securities or gambling.

Today, Gramm says that rather than loosening up regulations on bank holding companies, Glass-Steagall ‘was the first step towards making the Federal Reserve a “super-regulator.”’

Which is worse? You choose.

3. Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan was an ardent free-market proponent. That’s not a bad thing in itself, but Greenspan chose to ignore several powerful signs that housing was a bubble and the free market actually needed to be reigned in. By refusing to heed warnings (an attentive Greenspan might have required bigger down payments, stricter underwriting, or mortgage insurance) Greenspan let the crisis foment.

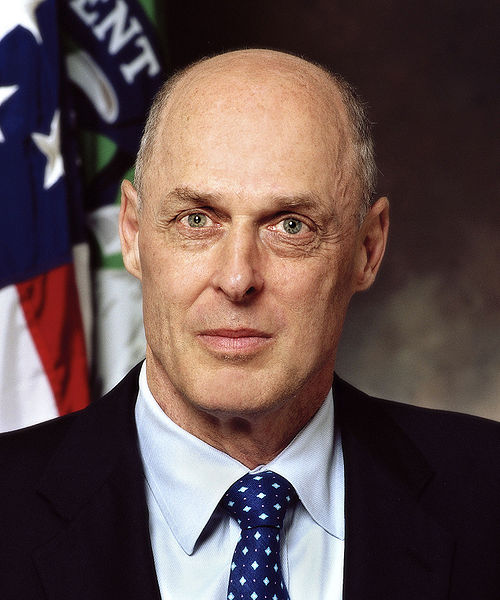

2. Hank Paulson

Former Secretary of the Treasury Hank Paulson is the poster child for what happens when conflicts of interest go awry. Paulson was CEO of Goldman Sachs from 1998-2006. Next, he revolved into a new position as Secretary of the Treasury, which came with a $200 million tax deferral. Once there, he simply kept acting like the CEO of Goldman Sachs.

Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi points out that Goldman Sachs was AIG’s biggest credit default swap customer, holding $20 billion worth of the crappy assets. If AIG went down, Goldman might go with it. Paulson couldn’t allow that to happen, which might explain why he hired ex-Goldman board member Edward Liddy to head AIG, and former Goldman VP Neel Kashkari to administer the government’s TARP program. The aggregate result of Paulson’s mess is billions in unaccounted-for bailout funds, government contracts for more of his Goldman friends, and a legacy as the wrong man for the job.

1. Joe Cassano

AIG Financial Products’ Joseph Cassano didn’t invent CDSs, but he did transform them into a worldwide phenomenon. He guaranteed buyers that AIG would compensate them if the credit obligations went belly-up. He did not, however, require that buyers show any money upfront when they bought the CDSs. As a result, AIG sold about $500 billion in guarantees, but couldn’t cover them with any assets.

He also specialized in the “naked” credit default swap, in which neither buyer or seller actually have access to the loan. Rolling Stone’s Taibbi explains it:

Unlike traditional insurance, Cassano was offering investors an opportunity to bet that someone else’s house would burn down, or take out a term life policy on the guy with AIDS down the street. It was no different from gambling, the Wall Street version of a bunch of frat brothers betting on Jay Feely to make a field goal. Cassano was taking book for every bank that bet short on the housing market, but he didn’t have the cash to pay off if the kick went wide.

AIG bet that the housing bubble would never burst. But it did, resulting in the shell of a company that government vultures are still picking at today. It also ended Cassano’s glory days—after an estimated $280 million in compensation over the last seven years.