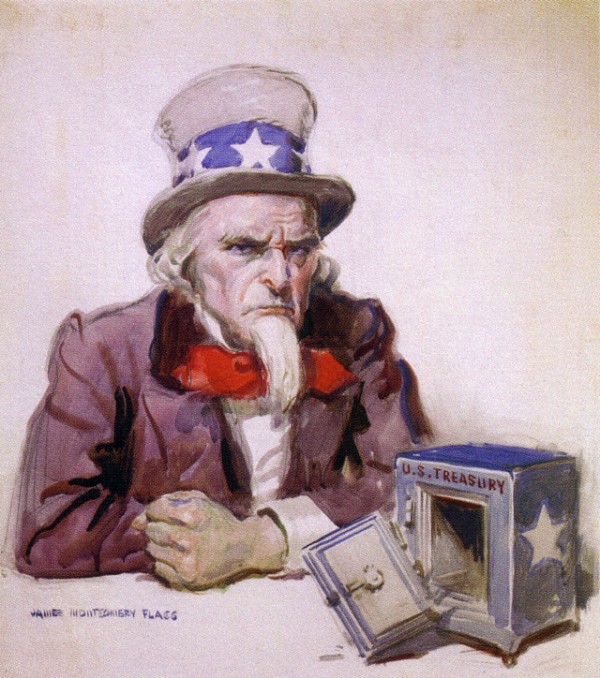

Painting by James Montgommery Flagg/1920

The US corporate income tax rate is 35%. Yet this year, Google, which made $5.5 billion in revenues, only paid an effective tax rate of 2.4%. Indeed, it’s not unusual for a corporation to pay only 6-7% in effective taxes.

Such numbers put you and me and most small businesses to shame. What gives?

It turns out that tax credits aren’t the only trick corporations use to evade taxes. From Intel to Bath & Body Works, most big American corporations have a subsidiary and income shifting scheme that radically skews the amounts they end up paying the IRS. Here are five of the main components that help corporations write pint-sized IRS checks.

Subsidiaries

Why make profits in your home state when you can move them somewhere with lower income taxes? Such is the rationale of many American companies headquartered in high-tax states. Strategies like the so-called Las Vegas Loophole let companies move profits to subsidiaries located in states like Nevada, which has no corporate income tax.

Chain retailers are among the corporations that love to set up subsidiaries. Wal-Mart, for example, set up an out-of-state subsidiary that “collects ‘rent’ from Wal-Mart stores, enabling the chain to disguise (an estimated $7.3 billion in profits over four years) as expenses,” according to this article. By paying itself rent via a real estate investment trust (REIT), Wal-Mart avoids additional taxes while keeping money inside the corporation.

Another trick is to create a trademark holding company in a state that doesn’t tax intangible assets like trademarks. Home Depot has a paper subsidiary in trademark-tax-free Delaware. This subsidiary collects large trademark use fees from Home Depot stores in other states, writes NewRules. Home Depot deducts those fees as a business expense, and voila, its taxes dive.

Transfer pricing

About half of the 50 US states have adopted combined reporting rules to clog the subsidiary loopholes mentioned above. Combined reporting requires companies to list all of their sources of profit, regardless of state, before figuring out their state tax burden.

For many companies, however, national combined reporting requirements aren’t an issue—they just create subsidiaries in international tax shelters like Ireland and the Cayman Islands. A tool called transfer pricing lets companies make profits in tax havens while allocating expenses to higher-tax countries, writes the OECD Observer.

A company can apply transfer pricing to a variety of financial categories, including interest rates, service charges, share sales, and depreciation. This fickleness makes transfer pricing a continued point of intense scrutiny for governments around the world.

Google’s “Double Irish” strategy is one popular transfer pricing scheme. Google created two companies in Ireland to execute this maneuver. One pays royalties to use intellectual property (expenses that reduce income tax in Ireland). A second, located in Bermuda, collects those royalties. The meat in Google’s sandwich is the Netherlands, where profits go on their way from Ireland to Bermuda.

“Irish tax law exempts certain royalties to companies in other EU- member nations,” according to the excellent Bloomberg article that describes Google’s acrobatics. “A brief detour to the Netherlands avoids…Irish withholding tax.”

If you think the federal government would want to sink its teeth into those profits by implementing an international combined reporting requirement, think again. The feds would rather get what they can without changing the law: Google and the IRS negotiated for three years before coming to “an arrangement” that let the company execute its transfer pricing strategy, according to Bloomberg.

Nowhere income

States can only tax corporations with physical facilities, or a “nexus,” within the boundaries of the state. Otherwise, federal law doesn’t let states tax corporations, according to NewRules. Just selling goods or services in a state without having a factory or other facilities there translates to no state taxes.

Corporations have leveraged this rule to the point of having “nowhere income” that is not taxable in any state. NewRules illustrates with an example: “…if Nails Inc. has all of its property and payroll in two states, but just 10% of its sales in those states, then it will pay state income taxes on only 70% of its profits: (100 + 100 + 10)/3. The other 30% will go untaxed.” Taxes are even easier to avoid in states where sales are more heavily weighted than, say, payroll or property, according to NewRules.

Nowhere income becomes more elaborate if you can pull it off internationally. Intel did just this in the early 2000s, according to CTJ.org. The company declared “millions of dollars in profits from selling US-made computer chips as Japanese income for US tax purposes.” This exempted it from US taxes. Meanwhile, a US-Japan tax treaty required Japan to “treat the profits as American.” That meant Intel didn’t have to pay Japanese tax, either.

Income shifting

No transfer pricing-subsidiary scheme is complete without income shifting. This happens when a company transfers or licenses its intellectual property to a subsidiary in a tax shelter. Any foreign profits based on that technology are taxed according to the subsidiary country’s tax law.

According to US tax rules, such subsidiaries must pay an “arm’s length” amount for those rights, the same mutually-agreed-upon amount any unaffiliated company would pay for them. So parent companies set that amount low to avoid tax burden, writes CTJ.org.

The nature of the loophole means that the feds can’t get lost taxes back, either. Bloomberg writes that “…multinationals that shift profits overseas are deferring U.S. income taxes, not avoiding them permanently. The deferral lasts until companies decide to bring the earnings back to the U.S. In practice, they rarely repatriate significant portions, thus avoiding the taxes indefinitely.”

Tax havens

Some tourist havens, notably Bermuda and Ireland, also happen to be stellar tax havens. “58% of offshore profits are now recorded in tax havens,” according to this FinFacts Ireland article. US operations, for example, have recorded more than $25 billion in profits in tiny Bermuda, which doesn’t charge any taxes, writes FinFacts.

It doesn’t matter that most of those multinationals’ sales happened in higher-tax countries like Germany, the US and the UK. Wherever tax rates are low, multinational profits rise, sometimes exponentially. That translates to tens of billions of dollars the US Treasury doesn’t get its hands on. US corporations, meanwhile, enjoy enviable tax rates, while the tax havens that house them benefit from the injection of foreign capital.