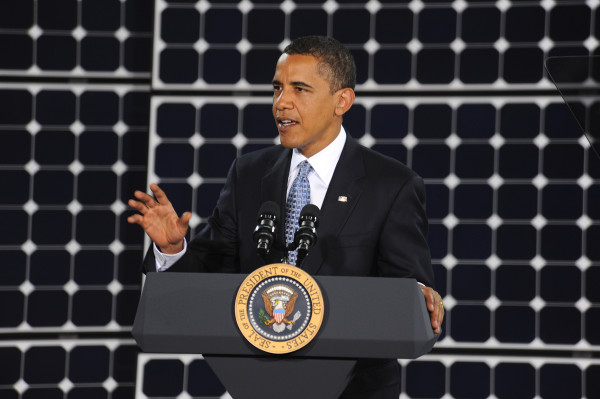

Over the weekend, President Obama announced an ambitious plan to combat climate change through a new regulatory structure that would set greenhouse gas emission targets for the states and give them several years to meet those goals. In a video released on social media late Saturday, the White House introduced the initiative in broad strokes and Obama is expected to unveil it in more detail during a speech Monday.

The Clean Power Plan would target power plant emissions and seems to promote a “cap and trade” style system nationwide, although each state would have a rather wide degree of latitude in deciding exactly how it meets the emission targets. Generally speaking, cap and trade would mean limits on pollution and the ability of businesses to buy permits allowing them to pollute over that cap. Conservative critics have, unsurprisingly, derided it as “cap and tax.”

That system, or any policy intended to undo an entrenched reliance on fossil fuels and shift energy consumption toward renewable sources, would necessarily involve big economic consequences. But climate change itself has the potential to negatively impact the economy.

Climate change and the economy

Climate change has been a major topic for years now, but there has been little political will to deal with it, at least on the Republican side of the aisle. That has to do with concern about the economic effects of policies meant to stymie man-made consequences on the environment as well as a tendency by many conservatives to deny those consequences. Since the GOP has dominated Congress for most of Obama’s tenure, there has been no major legislative resolution.

While challenging the fossil fuel status quo will likely impact the many jobs in that sector, failing to combat climate change will have consequences of its own. The Environmental Protection Agency, for example, has argued that reducing greenhouse gas emissions will have “important economic benefits” in cutting the long-term costs associated with climate change, mainly health-related. The Risky Business Project, headed up by former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and former Bush administration Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, has also investigated the economic risks of ignoring climate change and identified the following as the most critical:

Damage to coastal property and infrastructure from rising sea levels and increased storm surge, climate-driven changes in agricultural production and energy demand, and the impact of higher temperatures on labor productivity and public health.

Bloomberg even attributed Hurricane Sandy and its costly damages to the effects of climate change, saying that “storms, flooding, and heat waves are already costing local economies billions of dollars.” And last month, a report from his Risky Business Project identified the Southeast U.S. and Texas as being particularly threatened by global warming.

But not everybody agrees that these risks are existential or that Obama’s new rule on power plants would be a net positive. In analyzing an earlier version of the Clean Power Plan, Nicolas Loris of the conservative Heritage Foundation argued that the new rules would result in “higher energy bills for families, individuals, and businesses [that] will destroy jobs and strain economic growth,” and “have a negligible impact – if any – on global temperatures.”

Obama’s plan

The Clean Power Plan, as the Obama initiative is known, has actually been in the works for quite a while. It was first announced last year and builds off earlier EPA proposals. Monday’s announcement will unveil the final version of the plan, according to the White House social media accounts.

BREAKING: On Monday, @POTUS will release his #CleanPowerPlan—the biggest step we’ve ever taken to #ActOnClimate. https://t.co/BU1PF0wjUK

— The White House (@WhiteHouse) August 2, 2015

The goal is to increase usage of renewable energy through an incentive system that would raise financial penalties on heavy polluters. The president’s final plan would set a higher target for reducing carbon pollution, to 32 percent from the earlier 30 percent target. States will be expected to drive enforcement of the new rule, but according to the Washington Post, their “governments also will be given more time to meet their targets and considerably more flexibility in how they achieve their pollution-cutting goals.”

The White House released a fact sheet on Sunday ahead of the official announcement, backing up that commitment to flexibility and outlining some specifics of the new rule. States would be required to submit their plans for reducing carbon emissions by September 2016 but can request an extension of up to two years for final versions, and compliance would not be assessed until the 2020s. The administration also expects the plan to end up saving American consumers $155 billion altogether between 2020 and 2030, “reducing enough energy to power 30 million homes.”

In addition to those benefits, the proposal will almost certainly have widely-felt effects on environmental policy and energy industries. As The New York Times reported Sunday, “the regulations will set in motion sweeping policy changes that could shut down hundreds of coal-fired power plants, freeze construction of new coal plants and create a boom in the production of wind and solar power and other renewable energy sources.”

Monday’s announcement is just Obama’s first step in a renewed push this fall to combat climate change. According to The Hill, Obama is set to address the National Clean Energy Summit in Las Vegas later this month as well as a conference in Alaska on the effects of global warming there. Obama is also hoping for an international agreement during the UN climate change conference in Paris this December.

So, will it work?

Economically speaking, that seems a sound bet. If a cap and trade system is instituted, increasing taxes on businesses who pollute beyond the set cap should incentivize them to opt for reducing their pollution levels.

But that also depends on what those financial penalties end up being. If the costs of following those rules turn out to be higher than that penalty, firms may just opt to pay the fine and continue their current ways.

Beyond economic calculations that might hobble implementation, there is also the question of whether the rules, if followed, would substantially reduce emissions. As Vox’s Brad Plumer explained, the Clean Power Plan targets power plants and emissions from those sources “have already dropped 15 percent between 2005 and 2013 – thanks to a crushing recession, cheap natural gas pushing out coal, the rise of wind power, and improved efficiency.” Plumer also points out that in 2013, American power plants only accounted for about 30 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions and he calculates that the president’s plan will only cut overall emissions by about 6 percent by 2030.

This new policy, therefore, is not the whole story. Obama has implemented a number of environmentally conscious policies over the years, including increased fuel standards, and all of those together will ultimately determine how successful his administration is in arresting man-made changes to the global climate.

But there’s a rather large elephant in the room: the 2016 elections. Because these policies have all been initiated in the executive branch, they might not survive past January 20, 2017. Many Republicans, including several of the presidential candidates, deny climate change is even a problem worth addressing. And regardless of their views on the science, Republicans also challenge whether Obama’s policies are worth the associated economic costs. After all, it’s reasonable to expect that some bills might go up for at least a while during the transition phase, and it’s also rather obvious to expect lost jobs should the rules succeed in reducing reliance on carbon emissions.

But should that happen, something would have to take the place of those old power sources. Just as obviously as shuttered coal plants mean lost jobs, newly built wind farms or solar arrays would mean new jobs. And as The American Prospect found, the dire warnings of the costs of environmental regulations are almost always overblown. For example, in looking at the effects of the Clean Air Act of 1990, environmental economist Robert Hahn predicted that “there are a minimum of several hundred thousand jobs…at risk” with his best-case estimate being 20,000 lost jobs. Instead, seven years after the law went into effect, the number of people benefiting from a provision of the law aiding displaced workers stood at only 7,000.

Markets, it turns out, tend to be quite flexible, and regulations also have benefits that their critics discount or ignore altogether. Jobs might be lost due the Clean Power Plan rules, but presumably new jobs will also be created if it succeeds and creates a booming market in renewables. And, more indirectly but no less important, cleaner air would mean healthier people and thus lower medical bills and an overall increase in social welfare.

But we might not get a chance to see if that rosy scenario comes to pass. Many Republican state officials have made clear they intend to challenge the Clean Power Plan in court. And even if it survives those challenges, a Republican president could undo it very quickly. For those reasons, the key factor in determining whether Obama’s legacy on climate change is a successful one may very well be Election Day 2016.