2011 marked the first time in years that a labor dispute — in this case, Wisconsin’s public employees being stripped of their bargaining rights — captured national media attention. The dramatic progression of events, which are detailed below, provided fodder for dinner conversations and pundit diatribes for weeks.

It also brought to light, in some ways, the weakness of labor unions against the American government. For all of the gains that labor fighters have made, more and more concessions have been made in the past forty years. Unions are at a weak point in this country, unable to protect workers from layoffs or cuts in their benefits. Organizers are hoping that the dramatic bust in Wisconsin may become a rallying point, inspire a new generation of organizers.

In the meantime, we’ve compiled a list of ten other labor protests from the dramatic history of American labor, starting from the 19th century and ending in the present day. Many of them were, technically, failures: strikes that were busted, protests that ended in bloodshed, activists that were convicted in sham trials. However, without these protests and movements, American workers wouldn’t be enjoying the benefits that most do have. The fight for labor rights didn’t end with these protests, and it won’t end now.

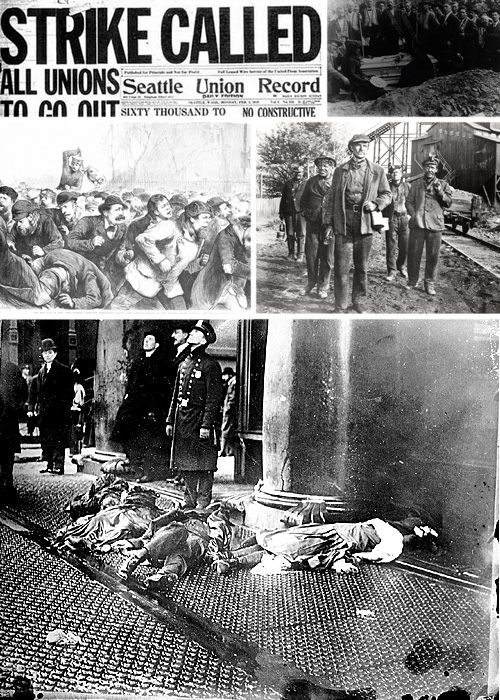

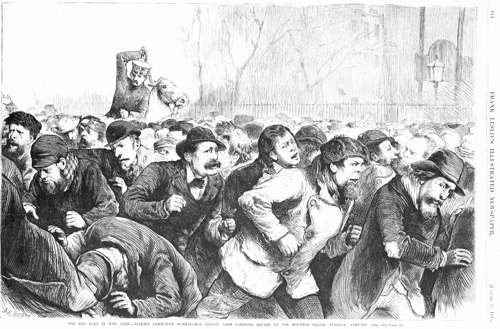

1874: The Tompkins Square Riot

Fifty years before the Great Depression, there was the Great Panic: a fall in the demand for silver triggered a worldwide depression that lasted from 1873 to 1879, with high unemployment, bank failures, and business closures.

Unemployed workers organized a march from Union Square to Tompkins square, protesting for the city and state government to create more jobs. On January 13th, 1874, roughly 10,000 showed up for the march, not knowing that the city had secretly revoked their permit the night before. Hundreds of police, both on foot and horseback, met them, indiscriminately beating down men, women, and children.

The riot culminated in 46 arrests, and a loss of momentum in the unemployed movement. Strengthened by their success in dispersing the protestors, the NYPD increased its surveillance and harassment of other political organizations.

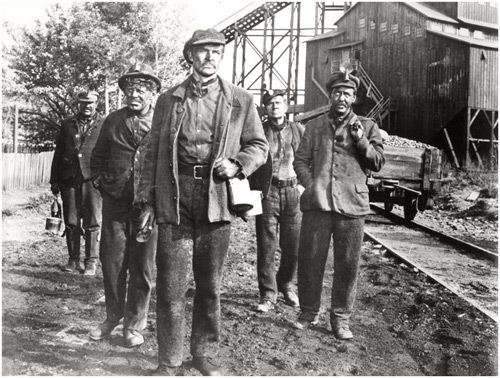

1877: The Molly Maguires

The Molly Maguires were a secret Irish-American organization, affiliated with the Ancient Order of Hibernians. The name evoked a sort of boogeyman in the mainstream American psyche: that of the illiterate immigrant, whose loyalties and morals were questionable, and who wanted to rise above his proper station in life. The Chicago Tribune called them “a secret, oath-bound organization controlled by murderers and assassins.”

In the 1870’s, coal miners in Pennsylvania began organizing for better wages and working conditions. Franklin Gowan, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, and of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, hired detectives to investigate into the union, and into the violence that had erupted between workers and their supervisors. One detective, James McParlan, spent two years undercover among miners, and eventually testified that twenty of the men were Molly Maguires, and had been responsible for much of the violence. Ten of the men were hanged. Gowan used the name and fearful reputation of the Molly Maguires to crush the burgeoning union, and incited vigilantism against Irish immigrants and the striking workers.

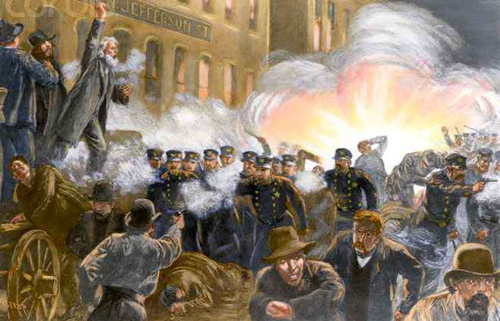

1886: The Haymarket Massacre

In 1884, The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions set a goal for obtaining an eight hour work day as the national standard by May 1, 1886. As the day approached, unions all over the country prepared to go on strike. In Chicago, where the movement was based, 40,000 workers went on strike. Over the next few days, thousands of protestors — unionists and their families, anarchists, socialists, and reformers — would clash with the police. On May 3, police at the McCormick reaper plant fired into an unruly crowd, killing two men and bringing tensions to a boiling point.

The next day, another rally was held in Haymarket Square, to protest the police’s violence. Close to 180 policemen were stationed in the square, ready to wade in to the crowd at the first sign of rioting. The rally seemed to be peaceful enough, until about 10 at night, when one speaker urged the crowd to “throttle” the law. At that point, the police force ordered the remaining protestors to immediately disperse. Someone in the crowd threw a bomb at the gathered officers, killing one immediately. Police drew their weapons and fired wildly, indiscriminately. Eight policemen died and sixty others were wounded, mostly by their own fire, and an indeterminate number of protesters were killed.

Hundreds of people were arrested, as newspapers published theories of anarchist conspiracies and calls for revenge, inciting hatred against immigrants and radicals. In one of the worst miscarriages of American justice eight men were put on trial for murder. There was no credible evidence against any of the defendants, and all of jurors confessed to prejudice against them. They were found guilty, and seven were sentenced to death. Four were executed, one committed suicide, and the two others had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. The two living men were pardoned seven years later by Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld. It was political suicide to do so, with popular opinion still vilifying anarchists and agitators, but Altgeld said, ‘No man has the right to allow his ambition to stand in the way of the performance of a simple act of justice.’

1910: The Garment-Workers Strike and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

By the 1900’s, half of New York’s population were foreign-born immigrants. Many of the female immigrants worked in the garment industry, supporting themselves and their families on low-paying jobs with terrible working conditions.

Labor leaders organized a walkout of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in September of 1909, after a group of employees was fired for trying to unionize workers. Five weeks later, one of the strikers, a nineteen year-old Jewish woman named Clara Lemlich spoke out in a packed meeting, telling of the indignities of working in the garment industry. Her speech led to a city-wide general strike, with 20,000 workers walking off their jobs. Images of young women being intimidated by police and company thugs inspired public support, even among New York’s upper classes, for the workers. The companies bowed to public pressure, and agreed to negotiate with the newly unionized workers.

The unions won many of their demands, in an unparalleled victory for labor organizers. Most of the companies, however, including the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, remained in the hands of their unscrupulous owners. It took the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire for the City to impose safety standards on industrial buildings. The fire, which took place only a year after the strike, is remembered as one of America’s most horrific industrial accidents, killing 146 workers, most of them young women in the teens and early twenties. The factory’s manager had a policy of locking his workers into the floor, citing concerns of productivity and worker theft. Many of the girls were left with no choice but to burn alive or leap to their deaths on the sidewalk.

1914: The Ludlow Massacre

Coal mining is one of the world’s most dangerous jobs: in the US alone, about 300 miners have died in accidents the past ten years. That’s not counting deaths from the diseases associated with mining, such as black lung disease.

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, coal miners and their families lived in “company towns”, in which all the property and amenities — such as general stores, churches, and law enforcement — were owned by their employers. The system often resembled feudal townships, with the company exerting nearly total control over the miners’ lives. Ethelbert Stewart, a federal mediator on the Ludlow strike, commented that the miners were “prohibited from having any thought, voice or care in anything in life but work, and to be assisted in this by gunmen whose function it was, principally, to see that you did not talk labor conditions with another man who might accidentally know your language.” He then added, “That men have rebelled grows out of the fact that they are men.”

The United Mine Workers of America began organizing in Colorado around the turn of the 20th century. The union chose to focus on workers for the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, which was one of the most powerful corporations in the company at that time. In 1913, they successfully organized a strike of 11,000 workers, who were demanding safer working conditions and changes in wages; in particular, they wanted to be paid for “dead work”, such as shoring up mines to protect workers from cave-ins, rather than just by the tonnage of coal they produced.

The miners were immediately evicted from their company-owned houses, and the UMWA organized tent colonies for the workers and their families, usually near mine mouths in order to block strikebreakers. Company-hired thugs fired random shots into the tent cities, and patrolled their perimeters in armored cars with a mounted machine gun. After a months-long standoff, the strike culminated in a sudden attack on the camp by a company-organized militia on April 20, 1914. The militia fired a machine gun into the camp, and burned the tents. Two women and eleven children suffocated to death in one fire, and several of the camp’s organizers were captured and executed. Nineteen people died that day. The massacre sparked off even more fighting between miners and company guards, killing dozens before President Woodrow Wilson called in federal guards to subdue the fighting.

1916: The Everett, WA Massacre

The IWW has always been one of the more radical and socialist-leaning labor organizers in America. It was founded as a counterpoint to the American Federation of Labor, contending that all workers should stand united with each other, taking possession of the means of production and abolishing the wage system. To many in America, particularly businesses and politicians, the Wobblies represented a dangerous and seditious group, particularly after they came out in protest of America’s involvement in the first world war.

On November 16, 1916, two boatloads of Seattle-based Wobblies set out for Everett, a small town in the northern bend of Puget Sound, to show support a group of striking shingle weavers. They were met by a force of over 200 men, many of them who had been deputized by Everett’s sheriff for the occasion. The Snohomish County Sheriff, Donald McRae, drew his gun as the first boat drew into port, and asked who the leader of the group was. The IWW men famously answered “We all are!” A shot was soon fired, though which side shout first has always been disputed, and the whole scene quickly devolved into a shootout. The Wobblies were largely, but not completely unarmed, and when the firefight finally ended, two deputies and between five and twelve IWW men were dead.

The boats reversed out of the port and returned to Seattle. When they landed, police arrested 74 Wobblies, and charged one of them, Thomas H. Tracy, with murder. Tracy was later acquitted. This was the beginning of the end for the IWW in America, however. The US government used WWI as an excuse to crush the movement, and incite attacks against the workers elsewhere in the country, effectively crippling the organization.

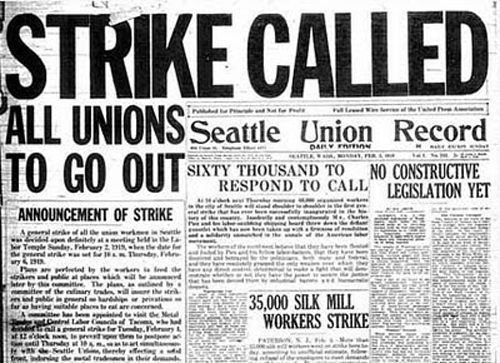

1919: The Seattle General Strike

During the two years that America was involved in the first World War, wages were controlled in order to keep inflation down. After the Armistice in 1918, employers were reluctant to raise wage scales back to their pre-war rates. In Seattle, disgruntled shipbuilders started agitating for a higher wages for workers. When the company rejected their demands, 35,000 workers went on strike on January 21, 1919.

Other unions in the city showed almost unilateral support for the shipyard workers, testifying to the Seattle Central Labor Council and calling for an immediate general strike. On February 6, almost 25,000 union members across the city walked off their jobs, effectively paralyzing the city. Different committee were formed, working to distribute food and provide essential services, such as garbage removal, to the city’s people. The strike, which lasted for a week, was peaceful. No arrests were made in connection to the protests.

Seattle’s mayor Ole Hanson called in federal troops, supposedly to “restore order”, and waged a war of words on the movement, using the specter of communism to scare away popular support. Labor organizers began to get nervous that the general strike would set back their efforts in the city, and union members began to go back to work. By February 11, the general strike was over.

After the strike, Seattle’s Mayor retired from politics to become a lecturer. He took credit for dismantling an attempted revolution, while state and federal governments used the strike as an excuse to pass anti-syndicalism laws. The new laws set a precedent for increased harassment and arrests of radicals, and eventually became the fuel for the First Red Scare.

1920: The Battle of Matewan

Matewan, West Virgina, is a small town on the Tug river, right near the Kentucky border, deep in coal mining country. Like with the Ludlow strikers in Colorado, the miners lived in company towns, earning low wages under harsh conditions. The UMWA began organizing coal workers in southern Appalachia in January, and by that spring, 3000 men had signed on. Both the police chief, Sid Hatfield, and the mayor of Matewan openly supported the miners in their efforts to organize, a rarity on this list.

On May 20, thirteen detectives from the Baldwin-Felts Agency arrived in Matewan. They had been hired by the coal companies to evict union workers from their company-owned houses. Word of the evictions spread rapidly through the town, and a crowd confronted them at the railroad depot.

Chief Hatfield attempted to arrest one of the detectives, and the detectives resisted. Someone fired a shot, and the two sides exchanged gunfire. When it was over, two miners and Cabel Testermen were dead, as well as seven of the detectives. Sid Hatfield became a folk hero to Appalachian miners, and then a martyr when the remnants of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency assassinated him in Welch, West Virginia. The killing sparked off a wave of violence between miners and company-hired strongmen. The violence culminated in the Battle of Blair Mountain, a ten-day insurrection by armed coal miners, and the largest armed conflict in the US, second only to the Civil War.

1981: The Air Traffic Controllers’ strike

The influence of organized labor waxed and waned in cycles in the middle of the century. The affluence of the 1920’s and rising anti-communist sentiment following the Bolshevik revolution in Russia curtailed it, while WWII saw a sharp rise in union membership due to war production. After the presidencies of Roosevelt and Truman, however, who had labor sympathies, a number of acts were passed that limited the influence and power of unions.

The final blow, in many ways, came in 1981, soon after Ronald Regan was elected president. Several unions, including the Air Traffic Controllers and the Teamsters, had supported Regan’s campaign after being disappointed by the Carter administration’s support of the FAA, their employers. On August 31, 1981, 13,000 members of the PATCO union struck for higher wages, a 32-hour work-week, and better working conditions.

Because the PATCO was made up of governmental workers, the strike was, by law, prohibited. Ronald Regan declared the strike to be a danger to national security, and ordered the strikers back to work. Only 10% of the strikers followed his order, while the rest continued to press their demands. Regan issued an ultimatum to the workers: return to work within 48 hours, or their jobs would be forfeit.

When the 48 hours were over, Regan fired the 11,345 air traffic controllers still on strike and blacklisted them from further federal service, ushering in an era of renewed union-busting.

2011: Wisconsin Protests

Issues of labor were brought to the forefront of American discourse in February, with newly elected tea-party Republicans turning their focus on reducing union power. On February 14th, Wisconsin governor Scott Walker put forth his State Budget Repair Bill. The bill proposed increased payments by state employees to cover healthcare and pension costs, and stripped out collective bargaining rights. Without these rights, state employees’ unions would be unable to bargain for working condition policies, such as overtime, health care and pensions, health and safety, and working hours. The only thing public employees’ unions would be able to bargain for would be wage scales.

Walker rejected Democrats and union leaders’ offer to accept the bill without the collective bargaining amendment, saying that it “stood in the way of local governments and school districts being able to balance their budget.” State Democrats left the state on February 20, leaving the state legislature without enough senators to pass a fiscal bill.

Protestors flooded the capitol in the tens of thousands; as many as 70,000 protestors were reported on February 19, growing to 100,000 a week later. Other protests were staged around the country in solidarity. The protests were entirely peaceful; there were no arrests, citations, or property damage, according to Madison police force spokesmen.

It was a month of long, nasty political dealing: Walker attempted to con and threaten the missing Senators into coming back, while alternatively belittling and intimidating protestors. On March 9, in an underhanded move, the state Senate stripped the bill of all fiscal measures, which meant that they could pass it without a quorum. And pass it they did, in an 18-1 vote. A judge immediately issued a stay on the bill, and the Attorney General has vowed to fight for an appeal. The status of Wisconsin’s public employees’ rights are still up in the air, but many have vowed to continue to fight.