Vultures have always had a place in the economy. From time immemorial, regular citizens have scraped by on scavenged goods. Being a vulture today may involve more connections and paperwork, but the basic premise is the same: Profit off something that’s floundering, dead, or simply unclaimed.

We’ve compiled a short list of the ways vultures are making a killing today, despite (or perhaps because of) the recession.

Vulture capitalists

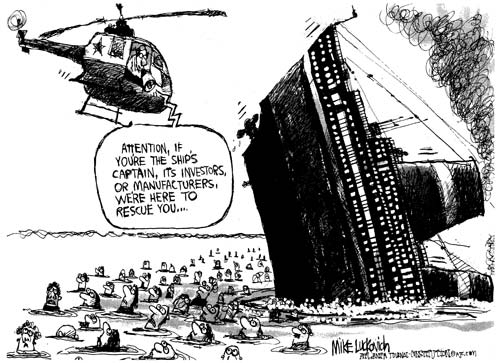

When a company is close to dying, some people just won’t let it rest. These company flippers, or vulture capitalists, buy distressed companies, clean up their operations, and resell them for a handy profit. Some of these vultures lay off employees as a part of restructuring the company, earning them a questionable Main Street reputation.

Vulture funds

Image: mape s/Flickr

These hedge funds prefer to be known as distressed-debt funds, but the activity is the same. A developing country is about to write off its debt, or its bonds are losing a lot of value. A vulture fund buys the debt at pennies on the dollar (or whatever currency that country is running). Bondholders, afraid of losing their entire investment, sell their bonds to the vultures and make a cleaner break than they would have otherwise. Some vultures then either sign a legal agreement with the country to repay the full balance of its debt and interest, offer the vulture an ownership stake in some of the country’s industries, or some other such goody. Some vultures resort to suing the country for the value of its debt and interest. Needless to say, you need to be extraordinarily well-connected to pull off this kind of carrion-eating activity.

In most cases, the vultures get what they came for, and the country doesn’t default.

Vulture collectors

If anything has been plentiful during the financial crisis, it’s bad debt. For banks, debt turns into a liability after a certain period of no payment. In order to get that bad debt off their books, banks have been dumping it at a huge discount.

There’s so much bad debt that in-the-know Main Streeters have been getting in on the action. Organizations like the National Loan Exchange offer deals daily; people also frequent their local (smaller) banks for the stuff. They take out a loan, buy the debt, then figure out a way to collect on it. If they can collect on enough of the debt, then even after they pay off their loan and give the collection agency a chunk, there’s profit to be had.

Of course, the bigger your portfolio, the better. There are no guarantees in this game. But I’ve seen enough people do it—a la the controversial Bill Bartmann–that I can say something’s working.

Vulture real estate investors

If you’re Joe Schmoe looking for a rehab, the market might not be as easy as you think. This is because professional real estate investors are working hard to buy the deals before you do, smack on a new layer of paint, and sell it to you “turnkey” at a higher price. If a real estate investor can get her hands on a good foreclosure and flip it quickly, she can make a handy profit.

The key here is speed. Oftentimes, before Joe Homebuyer even sees a house, real estate vultures are at the auction block or calling homeowners who seem distressed to snap it up first.

Domain vultures

Image: coniferconifer/Flickr

Let’s say you finally registered that trademark for Wellbeing Widgets. Your widgets show promise in the market. You’re ready to hit the big time with a website.

Except that some other weasel already owns wellbeingwidgets.com. And widgets.com. And wellbeing-widgets.com, and so on. Said weasel isn’t doing anything with the domain, but is willing to sell it to you at a gouged price.

This happens all the time. When the economy improves, however, and people start registering more business names, it might especially hurt.

Your trademark, your name, variations on your name, and even misspellings of your website can be squatted upon. It’s illegal, but rarely enforced. A similar kind of under-the-bridge operation is the patent troll, who buys up a lot of patents with no intent of actually making them, then charges the companies who actually manufacture them a fortune for the patent.