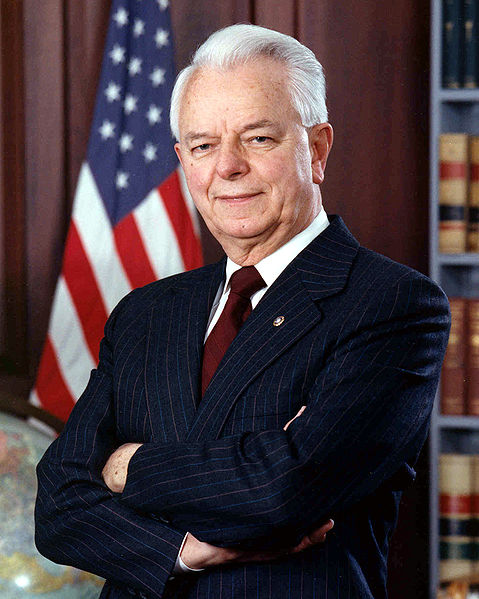

Robert Byrd, the longest-serving senator in US history (1959-2010), passed away today. The longtime West Virginia representative left a long, colorful, and impressive leadership career in his wake. Here are five leadership lessons from the illustrious senator’s life and career:

1. Don’t forget your humble beginnings. Instead, use them to your advantage.

It’s part of the Great American Story that everyday folk from humble beginnings can hit the big time as CEOs, entrepreneurs, or politicians. Robert Byrd grew up in a poor West Virginia coal mining community. He worked as a meat-cutter during the Great Depression, making $28.66 every two weeks, according to USA Today. He had to drop out of college due to lack of money, but later earned a law degree by taking night classes while working in the House.

But when he made it in politics, he “never forgot where he came from,” according to this Washington Post narration. He delivered “all kinds of benefits, programs, buildings, money” to them, earning himself a reputation as the King of Pork. But West Virginians kept paying him back by voting him into office. Byrd stayed in tune with his beginnings–and used them to his advantage.

2. You can make very bad decisions and still have a successful career.

Let’s face it. Joining the KKK is a bad idea, in politics and in life. But that’s exactly what Byrd did in 1942, in his early 20s. He was soon elected his KKK unit’s “Exalted Cyclops,” or unit leader, according to this Washington Post article (also the source of the next paragraph). He continued recruiting for the Klan for about a year. In 1945, he wrote a letter complaining about the Truman government’s efforts to de-segregate the military.

When Byrd ran for the US House in 1952, his KKK affiliations surfaced and almost ended his career. But Byrd pressed on. Still a racist, Byrd voted against the Civil Rights Act in 1964, filibustering the bill for more than 14 hours. He also voted against the Supreme Court nomination of Thurgood Marshall.

Byrd, however, changed his stance on race over time. He went on to become Senate Majority Leader twice, and, as we now know, the longest-running Senator in history. He admitted that the KKK remained a black mark on his record, but it ended up not hampering his career. He apologized, showed that he had changed, and people stuck with him.

3. If your decisions were bad enough, though, they’ll haunt you to the end.

In his early 20s, Byrd was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. This pigeonholed as a Southern racist in politics–which, for a while, he was. Later in his career, however, he expressed deep regret at both his KKK affiliation and his vote against the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Despite his long and, by most accounts, successful career, Byrd’s KKK affiliation never quite disappeared. “I know now I was wrong. Intolerance had no place in America. I apologized a thousand times . . . and I don’t mind apologizing over and over again. I can’t erase what happened,” writes the Washington Post. Although Byrd changed over time, the Klan would haunt him until the end.

4. Don’t stop taking risks.

In 2003, at the ripe old age of 85, Byrd became the Bush Iraq war’s strongest congressional critic, according to USA Today. TV stations, the online community, and hoardes of young Democrats stepped behind Byrd, reviving his political reputation.

Taking a strong stand against Bush represented a political risk for Byrd. It made him enemies. But Byrd followed his convictions anyway. This won him fans and revitalized his career. This is a good reminder that in many organizations, always following the status quo is a sure way into oblivion.

5. If you’re lacking in one area, make up for it by being twice as strong in another.

“Dour and aloof, a socially awkward outsider in the clubby confines of the Senate, Mr. Byrd relied not on personality but on dogged attention to detail to succeed on Capitol Hill,” writes the Washington Post. He was the “go-to guy” for questions on how the Constitution and the government worked, says the Post. “He saw himself both as institutional memory and as guardian of the Senate’s prerogatives.” Byrd wrote a 4-volume history of the Senate and kept a copy of the US Constitution in his pocket.

This encyclopedic knowledge gained him respect among his peers and informed his political positions. Byrd made up for his social disadvantages by making himself indispensable in other wise. He essentially created a valuable niche for himself.

Anecdotally, USA Today sums up how Byrd’s lifestyle nourished his expertise:

Since entering the Senate in 1959, Byrd has been to a movie theater only twice; the last time was to see a second run of the 1956 classic The King and I. He doesn’t play golf. “I have no hobbies other than to read,” he says. Byrd devours histories, biographies, the Bible, even the dictionary. He can quote long passages of poetry from memory and recount historical events in minute detail without checking a book. “His is the most prodigious mind I have ever known,” says Sen. Ted Stevens, an Alaska Republican.

R.I.P., Senator Byrd