Image: dktrpepr/Flickr

In order to be heard, you need to interrupt.

In order to share an idea in a corporate setting, you need to be fast.

If someone misunderstands you and does a project wrong, it’s your fault for not communicating right.

This is American Business Listening 101. We rush through ideas because time is money. We interrupt one another in meetings because we want to prove our mettle. As a result, we waste hours of time and execute projects ineffectively.

If we could actually listen, we’d streamline communications within our teams, produce more accurate projects for leaders, even sell more to clients. So why don’t we do it?

Because we don’t know how. That’s what Marian Thier, who runs the consulting, coaching and training organization Expanding Thought, wants us to know. An expert in teaching businesspeople new ways of thinking, Thier recently realized that we have a serious listening deficit. Her new mission is to educate people about what listening is, why it’s important, and how we can become better at it.

I caught up with Thier to learn more about the art and science of listening. Here’s what she had to say.

BP: Can you talk a little bit how lack of listening skills could derail a leader?

Here’s the most important thing a leader does: A leader makes decisions. If you don’t listen fully, you don’t’ get all the information you need to make a good decision. That’s one way leaders are derailed.

Another responsibility of a leader is to be able to model behaviors. People coming up in the organization learn from the way you as a leader behave, so you best be an effective model.

When you don’t listen fully, others are also apt to lose their attention. So they leave a lot of information on the table that’s readily available to them. Because they are not appropriately listening to the situation at hand, they miss stuff and often make partially informed decisions.

Poor listening skills also prevent people from questioning, so they are not very critical in their thinking. They take things at face value. They trust the person who’s talking rather than being able to analyze and diagnose the value of the information that’s being put on the table.

There’s just too much that’s lost because they a) don’t know how they listen, and b) don’t know if how they’re listening fits the situation.

BP: It sounds like learning to listen could save time and be a competitive advantage, because you would be so streamlined and efficient.

Totally. But if so much is riding on it, how come people aren’t trying to develop those skills?

When I started to beta test this research, I learned that we form habits around the way we listen. Those habits become ingrained. We become very reliant on them without questioning whether that habit serves us well in a particular situation.

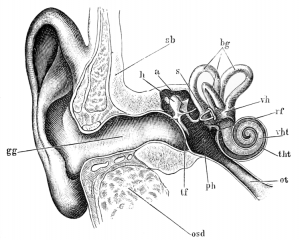

So how does that habit form? Brains begin to develop neural pathways very early in our lives. When information comes into the ear, the brain co-opts that information and takes it into an established neural pathway. Basically, our brains are pretty lazy. Our individual brains become wired for a certain kind of listening.

Another part of habit formation is physical. Say we’re on a tennis court. When I play tennis, I have established all sorts of physical habits. For example, when the ball is coming my way, my body and brain all say, “Okay, I know that this is a forehand shot, so get ready for it.” My opponent can read my posture to know where to place the ball. The same thing occurs when we’re listening. The body puts out signals that say, “This is the way I look when I listen.”

The next habit-former is psychology. When I get on the court and start thinking, “Oh no, something is going to hinder my back hand.” or “Oh gosh, this is a strong player,” I develop an emotional and psychological basis around all these messages. Same thing when you’re listening. You look at somebody as they’re talking and you might think, “That person reminds me of this really snappy boss I had, so I have to be very defensive when I listen, because if I don’t assert myself, I’m not going to get listened to.” Now you have another habit around something that has no merit, but it’s locked up into you habitual way.

And then the last consideration is our behavior. What are the things we actually do? There are people who do very specific things in their behavior. They interrupt, for example.

BP: Then you try to help somebody understand what interrupting really is?

Interrupting is really a part of the interaction. The interrupter has something to say and wants to share it. Good listeners hold off until the speaker has concluded, but interrupters don’t hold their tongue and break in, cutting off the train-of-thought and decreasing the amount of shared information.

BP: In every corporation I’ve worked in, especially the bigger ones, interruption and displays of assertiveness are ingrained in corporate culture. It’s like you have to be the top dog to be heard.

More true in the Western nations than in the East.

BP: So with that kind of culture, how can you even afford to listen if you’re so busy asserting your alpha status by interrupting everybody?

Probably the better question is, how can you afford not to listen? One of the things we’re doing in my company is educating people about preferred listening habits to help them grasp the breadth of the topic. Most people agree that listening is critical, but they really know very little about it.

To increase knowledge of the field and one’s self, I developed an assessment instrument that helps people understand which of four listening habits is their preferred habit.

To understand your habits is to raise awareness about how you listen. Part of the knowledge is being able to hold a mirror up to somebody and say, “This is the way you look when you listen. This is the way you attend when you listen. Is that the most effective way for you?” That’s question number one.

Question number two is to ask whether there are ways to be more effective as a listener. One way is to watch someone and say, “I watched you in this interaction and you interrupted the speaker eight times in ten minutes. What happened as a result of that?” That behavior is unconscious for most people.

BP: Could you talk a little bit more about the purpose interrupting serves, and what it means when people interrupt?

We can think faster than a person can speak. Thus, if someone is talking, instead of following them as they speak, we speed up our brains to move further ahead. We make assumptions about what that person is going to say and stop listening to what they are saying. The person who is supposed to be listening is actually not listening but is preparing to speak—to interrupt.

In a positive sense, interruption shows you’re engaged and you want to be additive. You want to inquire. You want to be a part of the conversation, but you’re not using your best skill—full-listening or turn-taking.

I teach people a tactic to use when they are in a situation and they want to interrupt. First, I ask, why is it you want to interrupt? What is behind it? If it is because you have a question, then just write down the question, then refocus on what’s going on. If you want to add your point of view, then write your comment down and keep listening. Chances are the speaker will cover the point you wanted to make or answer the question you posed, usually later in the interaction. Writing your mental disrupters ensures your thoughts are captured and enables you to remain focused.

Listening is the most respectful thing you can do. If you want to respect the person you’re listening to, tell yourself that maybe in 5 minutes that person will get to the point you want to make. Is there value in making that point? Or is it your ego that wants others to think you’re smarter than everyone else by raising an issue or inserting a comment?

Image: Simon Blackley/Flickr

BP: That was how I interpreted the chronic interruption that was going on in the workplace—ego stuff.

Yeah. In our workplaces we have:

a) very impatient people

b) high value for demonstrating our intelligence

c) a very male-oriented sort of way of interacting. It’s a game that gets played. Who can have the most control? Who can one-up others? Believe me, that’s a high-contact sport that results in many injuries of the hidden kind.

I observe a game I call “Who’s the smartest in the room?” I watch everyone in a discussion and award a “prize” at the end. After the interaction, I explain the dynamics I was observing. Then, privately, participants write the name of the person they think played the game most “successfully.” I tabulate the anonymous results and before I reveal the name I ask what the “players” learned from the game. I usually end by asking each individual what s/he did to be a contender for the title.

It’s rarely necessary to say the name of the person who “won,” because the offender almost always self-identifies.

A lot of this work is just helping people to be conscious about what they are doing. A huge amount is realized when someone can say, “I listen in this way.”. And then to be able to analyze the compatibility of the way they listen to the organizational dynamics. At that point someone can say, “I lose too much by not listening appropriately and I best devote time to skill development. That’s a simple formula. It’s not simple to effect, although easier than people thought.

BP: What about global implications?

If you look at Asia, for example, why is it that Americans who work in China have such a hard time there? Americans are fast-paced. They say “tell me in two minutes what it is, okay I got it,” and they’re ready to run off. While Asians complain about the lack of deliberation when dealing with Westerners.

In the West, there is the expectation that the speaker must make himself totally clear. The responsibility of the listener is to execute what the speaker is saying. If you don’t make yourself clear and someone else doesn’t execute properly, it’s your fault as the speaker, not the listener.

In Asia, it’s flipped the other way. The responsibility for listening is on the listener. I have to get from here everything I need in order to execute. So if something goes awry it’s my fault because I didn’t listen well. Think about how different the perceptions are and how those perceptions impact listening.

BP: That’s interesting. That’s how feel as a freelancer. I need to get everything right first in order to do the assignment properly. Otherwise, it’s my fault if anything goes wrong.

Good analogy. It’s the same way in corporations. You come back with this wrong product, all these people wasted their time working on a problem that actually wasn’t the right problem. They say, “You didn’t tell us the right thing.” Actually the issue went awry from the get-go because the parties involved didn’t have a clarifying interaction that was complete enough for both sides to tackle the assignment.

To remedy that problem, all involved need to be able to demonstrate that they’re clear. There’s a tool I teach people called a listening loop that helps people do that. It takes time to do.

People go, “Oh man, it takes too long.” Yeah, but how long does it take to fix the problems when you’re three months down the road and you’re doing the wrong thing? It’s much more expensive then than investing time at the start of a process.

BP: It sounds like becoming aware of the way that you listen involves a high level of coaching. Is there anything that people reading this interview could do by themselves that could help them become better listeners?

Absolutely. The first thing is to watch yourself when you’re listening. Say to yourself, “How engaged am I? At what point do I check out? What causes me to stop listening? What can I do to bring myself back so I can remain focused?” Observe yourself.

The other thing is to observe others. Try to see if you can pick up the signals they give you. They give you signals all the time about what they care about and what to listen for. Clues are in the kinds of questions that people ask.

For example, if you’re talking to someone who asks a lot of detailed questions, and you are a big picture thinker, you’ll probably shut off when that person gives you a lot of details. But your job is not to shut off. So if you observe that person asking detailed questions, you mirror by asking detailed questions, too. That way, you’re synchronizing with one another, rather than you each reverting to non-effective habits.

Observe yourself, observe others, and try to listen in the way that is compatible with another.

BP: I can see how you could train yourself to be a more effective person in general by adopting those skills.

Yeah. Many of the hundreds of people who have taken my assessment instrument Hear! Hear? tell me, “I never before thought about how I listen.” So just by being a self-observer you’re a leg up on developing capacity.

This is important work, but not daunting work. Here’s why. A habit is just that. It’s a habit. And it’s changeable. If you take any of the four elements that develop a habit and put energy towards changing it, it will change. Each of our listening habits is a strength. They are not deficits.

Sometimes what we need is to have more in our repertoire–to be additive. We’re not talking about stopping using a listening habit that serves you well, we’re talking about gaining access to others to broaden your capacity to listen well in any situation.

Official bio: Expanding Thought was founded in 1984 to help people think beyond the obvious. The firm does this through coaching, training and consulting initiatives. Marian and her staff work with individuals and organizations to think strategically and originally, and enable high-potential employees to fulfill their promise. Here is Marian’s blog on listening.