1987’s Wall Street was an instant classic. Its even, flowing pace was peppered by clever dialogue, convincing characters, and clean, almost mythological themes. Charlie Sheen’s Bud Fox, a hot young broker faced with an ethical dilemma, boldly sacrificed his career to do what he felt was right. Michael Douglas’ indomitable Gordon Gekko acted both as the movie’s foundation and its main highlight, making the movie’s coverage of 1980’s Wall Street complete.

1987’s Wall Street was an instant classic. Its even, flowing pace was peppered by clever dialogue, convincing characters, and clean, almost mythological themes. Charlie Sheen’s Bud Fox, a hot young broker faced with an ethical dilemma, boldly sacrificed his career to do what he felt was right. Michael Douglas’ indomitable Gordon Gekko acted both as the movie’s foundation and its main highlight, making the movie’s coverage of 1980’s Wall Street complete.

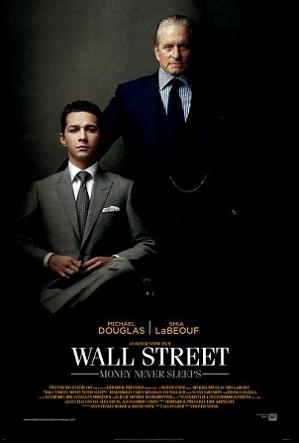

How can a sequel compete with that? In this case, it didn’t. Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps swapped out its predecessor’s killer dialogue and near-perfect pacing for a choppy arc, disparate plots, and sentimental moments as draggy as sandbags on an unpaved road.

The movie starts with Gekko being released from prison in 2002. He walks out alone into a world he no longer recognizes. Six years pass. In that time, Gekko has made a name for himself as the author of the book “Is Greed Good?”, which examines systemic greed in the US economy. Gekko appears to be a lonely and perhaps reformed man.

Meanwhile, doe-eyed Winnie (Carey Mulligan), Gekko’s estranged daughter, is dating bright young Wall Street broker Jake Moore, played by an almost-believable Shia LaBeouf. Moore works for the Lehman Brothers-esque Keller Zabel, where he is mentored by disillusioned managing director Lewis Zabel (Frank Langella).

A late-night Treasury meeting reveals that Keller Zabel is on the verge of collapse. Lewis, whose firm was trading at $75/share a week earlier, wants a fair buyout, but nobody wants to help. Bretton James (Josh Brolin), who runs the rival bank Churchill Schwartz, insults Zabel with a $3/share offer. Zabel claims it was vengeance for letting James’ company go under eight years ago (not unlike the old Salomon Brothers beef that came up again in 2008). The next morning, Zabel throws himself under a subway.

This devastates Moore, Zabel’s protégé. Unbeknownst to Winnie, he initiates contact with Gekko, seeking wisdom. After a hint from Gekko, Moore finds out that James profited from Keller Zabel’s collapse. Moore, seeking vengeance, spreads rumors that make James’ company lose $100 million.

James, impressed by Moore’s aptitude, offers him a job, which he accepts. In another meeting with Gekko, Moore learns that James probably helped put Gekko in jail for eight years. Gekko shares information on an offshore fund James is running; in exchange, he demands Moore to help him finally reunite with his daughter.

(Read about the rest of the plot here. Spoiler alert!)

These trade-offs culminate in one character’s loss and another one’s gain, followed by a more humane resolution.

The movie’s plot was complex and layered, but it didn’t execute well. Themes of greed, the 2008 meltdown, the aspirations of youth, social commentary, family drama, and general emotional sap coagulated into a choppy, ill-paced final product.

Michael Douglas’s Gekko, evil banker Josh Brolin, and the emotionally resonant Carey Mulligan stood out in the disparate kerfluffle. Supporting actors Eli Wallach, Frank Langella, and Susan Sarandon also carried their scenes. Cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto provided beautiful, sweeping views of New York.

The movie’s compelling, believable Wall Street culture was another strength. I got a kick out of the real-life references in the movie. Churchill Schwartz shorted the mortgage market years before the crash, a la Goldman Sachs in 2006. Keller Zabel, a Lehman-Bear Stearns hybrid, came complete with a Jimmy Cayne-like managing director who chose to walk his dog in Central Park the day his firm was collapsing. The handsome Bretton James invoked the essences of Jamie Dimon; his company the excesses and cunning associated with Goldman Sachs.

Still, as a whole, the movie never gelled. I was hoping for another classic, but this Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps is like having an everything bagel without schmear. Lots of flavors on the outside, but bland inside and lacking lubricant.