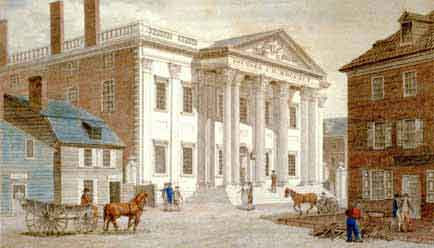

The United States was just a few years old when it faced a full-fledged financial crisis in 1792. The Bank of the United States was chartered in 1791 on the encouragement of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, a proponent of strong government involvement in the economy.

The young country’s finances had been “chaotic” following the Revolutionary War and Hamilton would call for the establishment of a national bank in 1790. After Congress approved his plan, the demand for subscription rights (or “scrips”) to shares in the new Bank of the United States was so strong it created a bubble that soon threatened the nascent American economy.

Hamilton would squelch that crisis by using Treasury funds to buy securities on the open market and stabilize the economy. But the trouble wasn’t over. Early the next year, after the Bank had officially opened, speculator William Duer would overextend himself trying to corner the securities market. His default would help spark a panic and Hamilton would use the kind of “lender of last resort” measures we’re familiar with today.

Economists David Cohen, Richard Sylla, and Robert Wright dubbed the Duer-led bubble-burst “Wall Street’s first crash.” The event helped create the New York Stock Exchange and essentially created “Bagehot’s rule” for dealing with financial crises eight decades before Walter Bagehot did.

The Bank of the United States had been highly controversial prior to its realization, and would continue to be for decades until its charter expired in 1811. The Second Bank of the United States would succeed it, but, equally controversial, find stiff political opposition from Andrew Jackson in the 1830s to be insurmountable and eventually die an unceremonious death itself.