The Gulf of Mexico oil spill is one of the worst company-created environmental disasters in history. Water and wetlands are sullied. People are dead. We’re still waiting on wildlife casualties and strange illnesses.

Amazingly, these themes are familiar. As long as mines and factories have existed, they’ve cut corners to save money, sprung leaks, and blown components. Consequences have ranged from curious smells to countless human deaths.

We’ve compiled the worst corporate environmental disasters in the world, from the mid-20th century to today. Some of these disasters have been going on for years. Others still haven’t been resolved. And as long as corporations continue to slither through accountability loopholes, BP won’t be the epitaph to this sordid pattern.

The Niger Delta

Image: Sosialistisk Ungdom – SU/Flickr

“Despite the country’s oil riches, much of Nigeria’s population suffers from fuel shortages”, wrote a CNN reporter in 2006 after a deadly explosion at a Nigerian oil pipeline killed 200 people. For Africa’s biggest oil-producing region, that statement says it all.

The ongoing disaster at the Niger Delta, the US’s fifth-biggest source of oil, almost makes the current Gulf disaster look innocent. There have been 7,000 oil spills there between 1970-2000, according to the BBC. That’s roughly 300 spills per year, writes Newsdesk, and “over 13 million barrels of oil. That’s the equivalent of one Exxon Valdez spill every year for 40 years.”

Explosions are frequent. The biggest one, in 1998, killed 1,000 people. Yet the government hasn’t gotten its claws into key perpetrator Exxon Mobile, and Nigerian people haven’t been able to land any settlements. Poor infrastructure, next to no wealth distribution to residents, and political upheaval keep the region in constant cataclysm. Big oil companies don’t mind–Shell blames militants for its leaks and explosions. As long as those hundreds of billions keep lining oligarchs’ pockets, the Niger Delta, it seems, will remain hapless.

Bhopal

Image: Simone Ippi

“Nobody knows how we suffered experiencing death so closely everyday … the rich and influential have wronged us. We lost our lives and they can’t spend a day in jail?”

So said Hamidi Bi, who expressed outrage over the meager two-year sentences handed down on June 7, 2010, to the seven men held accountable for the 1984 Union Carbide pesticide plant accident, which released toxic gases that killed more than 5,000 residents (activists estimate 25,000 died). An estimated 500,000 residents continue to suffer from birth defects, blindness, early menopause, and a host of other debilitating conditions.

Those seven men are out on a bail and will likely never see the inside of a jail cell. It’s a case of passing the buck that started that day in 1984 and reverberates 25 years later. In 1989, Union Carbide reluctantly forked over $470 million in settlement. Dow Chemical, which bought Union Carbide in 2001, feels the legal case is resolved. This is probably the reason Dow continues to ignore extradition requests to produce Warren Ghoeghan, the legal case’s “prime suspect.”

Amazingly, the Indian government continues to deny that any chemicals are at the site, despite evidence that chemicals are poisoning Bhopal’s water supply. And Dow continues its idiotic absolution of responsibility, while the Union Carbide CEO continues to hide out. Since all the bigwigs involved in this shameful event are sitting on their haunches, check out Bhopal.net to take citizen action.

The Gulf Oil Spill

From actors to politicians to environmentalists to fisherman and ordinary people like you and me, people are in a word, “pissed” about the Deep Horizon oil rig explosion. Clearly in over their heads, British Petroleum (BP) is no closer to plugging the source than it was when it first occurred on Tuesday, April 20, 2010.

In the first days following the explosion, BP attempted to minimize the extent of the damage. They went on record as stating that only a few gallons were leaking daily, and that every effort was being made to plug it up and end this disaster. What BP refers to as “a few,” as of June 8, 2010, is closer to between 20 and 40,000 a day.

Actor Kevin Costner swears he has the answer, President Barack Obama continues to be “frustrated,” Sarah “Caribou Barbie” Palin somehow sees environmentalists as the blame for this disaster. Meanwhile, the fishing industry and wildlife will be devastated for decades.

Who’s to blame? The list is too long to enumerate, but what matters now is whether BP can figure out the technology to plug this thing, and fast!

Lago Agrio

Image: Luigi Ochoa/Flickr

In 1964, Texaco started drilling in the Ecuadorian rainforest. The company eventually exported as many as 220,000 barrels a day to the US.

During this black gold rush, the Cofan, indigenous people who drink, bathe, and fish in the Amazon, began noticing a stench coming from the water. Texaco’s run-off system, in which “the pollutants come from a pool through a tube into the swamp and the swamp feeds the river from which the Cofan take their water,” didn’t seem to be working. Indeed, 18 billion gallons of run-off were found in the river–30 times the Exxon-Valdez spill.

Texaco defended the run-off system, saying that it was, “within industry standards.” Now the Amazon Defense Front is fighting back by representing the 30,000 plaintiffs who are tired of the damage to the river, cleaning up behind Texaco, and the unusually high levels of cancer they’ve been experiencing. As of May 2010, the damages sought were up to $27 billion.

Love Canal

In the 1940s, the Niagara Falls company Hooker Chemical began looking for a site to dump its “increasing amounts of chemical waste.” The Niagara Power and Development Company gave Hooker permission to offload its toxic junk in the Love Canal, an abandoned Niagara River canal that had turned into a municipal dumping site. For 11 years, Hooker dumped 21,800 tons of synthetics and chemical byproducts into the Love Canal site. After Hooker stopped dumping, they covered the site with dirt. Grass grew on top of the area, concealing the noxious chemistry set beneath.

Urban sprawl hit Niagara around the same time. Developers tried to build a school on top of the dump. Finding that they couldn’t, they built it–and an entire suburban neighborhood–close to the area (kids need a safe environment to grow up in, after all).

Nobody uttered a word about the waste until 13 years later, in the mid-1970s. A journalist investigation found residents presenting everything from “an alarming rate of miscarriages to tumors and birth defects.” After much hoopla, residents were finally “advised” to move, sell their homes back to the government, and pretend nothing had happened.

Hooker Chemical today is a subsidiary of US oil giant Oxy Petroleum. In 1995, Oxy paid Love Canal residents $129 million in restitution.

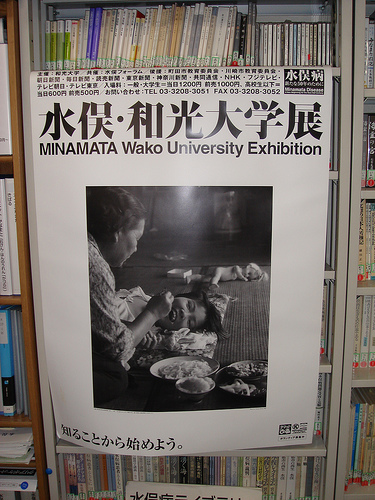

Minamata Bay

Image: Marufish/Flickr

In 1956, Japan’s Chisso Corporation was in the habit of dumping mercury into southern Japan’s Minamata Bay. When evidence surfaced that the mercury was giving locals neurological issues, Chisso vehemently denied wrongdoing. They then embarked on a curious combination of PR spin and a witch hunt.

Here’s how it worked. Chisso referred to the infected residents as poor, ignorant, and incapable of understanding science or research. Chisso enlisted the aid of doctors, whose pockets they lined, to back up their claims.

US photographer W. Eugene Smith did an exposé on the topic in Life Magazine, making the world and Japan’s Supreme Court aware of the continued poisonings, cover-up and pay-offs. Although it would be an unexpected career-ender for Smith–Chisso hired members of the Yakuza to “settle this once and for all”–it started a chain reaction that recently culminated in Chisso compensating victims’ families more than $80 million.

Probo Koala

Image: Greenpeace

What does an oil trader do when it has a boatload of “slops”? It charters a ship, hires an independent contractor and orders the contractor to dump them in Abidjan, the Ivory Coast. And what precisely are slops? That would be hydrogen sulfide, a highly poisonous gas that occurs naturally in crude petroleum.

And why would Dutch-based Trafigura dump these slops in the Ivory Coast? Hmmm, do you want the truth or would you prefer their spin on things?

Let’s take option number two. In response to an article that appeared in The Guardian on May 14, 2009, Trafigura says that Compagnie Tommy, the contractor, acted on its own when it set sail to Nigeria to drop off some oil cargo, then went to neighboring Abidjan and dumped slops.

The spin goes on to deny that it’s impossible the slops, dumped in August 2006, could have caused the deaths it did. It also denies that slops could have anything to do with the thousands of people who had everything from diarrhea to upper respiratory illnesses.

But Trafigura must not believe its own spin. The company, after denying damages, suddenly agreed to settle for $198 million.

Ok Tedi

Image: Ok Tedi Mine CMCA Review

50,000 residents live in 120 villages, along 500 square miles of the Ok Tedi River in Papua New Guinea. A mining company named after the river—Ok Tedi River Mining, Ltd.—has forever altered their way of life. Ok Tedi River mining has been dumping about 90 million tons of waste per year into the river.

Australia’s BHP, 52% one-time owner of Ok Tedi Mine, dreamed up an ad campaign declaring the waste to be “virtually identical” to natural sediment. Four years later, BHP released a statement “regretting” the comparison. The residents rejected their apology, sued BHP and won $28.6 million. In 1999, BHP dissolved their ownership in Ok Tedi Mining, admitting that they were not compatible with BHP’s environmental values.

Curiously, to this day, Ok Tedi continues dumping toxic waste into the river. The mine will close in 2012. It’s expected to take only 300 years to clean up the waste.

Esperance

Image: Halok

It’s difficult enough to fathom that a company knowingly broke environmental laws and endangered the lives of people. When the government turns a blind eye and is almost complicit, it’s unconscionable.

450 miles from Perth, Australia lies the 14,500-resident town of Esperance. Outside of town, a mining company named Magellan Metals extracts, removes, and transports lead. Magellan is required to transport lead within strict guidelines, so that nobody inhales or ingests it.

The West Australian Government admits to knowing two years prior to the mine’s opening that it failed to properly load and transport lead through Esperance. It took the death of 4,000 birds, tainted drinking water, and off-the-charts blood levels of lead in local residents to convene an inquiry.

Explaining its actions not to prosecute, officer Ann Stubs with the Department of Environment and Conservation said, “Prosecution of the offence is not recommended as it appears not to be of a deliberate nature or to have resulted in environmental harm.” Pardon me while I choke.

Exxon-Valdez

Long before Deep Horizon in April 2010 there was Exxon-Valdez. In 1989, the Exxon-Valdez, carrying over 1.2 million barrels of oil, ran aground in an attempt to avoid glaciers as she passed through the Valdez Narrows. 257,000 barrels spilled into the narrows and several surrounding beaches.

Exxon shelled out (no pun intended) $2.1 billion, employed 10,000 people and 1,000 boats over four summers to clean up the spill. Nobody determined exactly what caused the spill, but a drunken captain and disobedient ship’s mate were suspected. It’s all semantics, though, and of little comfort to the fisherman and wildlife who have to share their environments with sludge. An estimated 23,000 gallons remains on area beaches.

Meanwhile, the Exxon Valdez is now a Panama-registered Chinese ore carrier known as the Dong Fang Ocean.

Heard the expression “no nukes”? It came about as a result of a partial meltdown of a nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island in Middleton, PA in 1979. Although nobody was killed or even injured, the plant was shut down. But this wasn’t until after the usual dog and pony show.

For some unknown reason, a failure occurred in a non-nuclear section, when the main feed-water pumps ceased operating properly. This caused a chain of events from systems shutting down to coolants failing to cool to the eventual overheating and meltdown.

Depending on who is telling the story, federal and state authorities and regulators, including the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, reacted promptly or were slow to jump into their sweats and check out the problem. Again, depending on who you’re talking to, either no long-term effects have been suffered by those “in the neighborhood,” or Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma has been reported in several cases of people within a 3-mile radius. No pun intended.

To this day, the plant is no longer in operation.

Seveso

In 1976, Italy-based Roche subsidiary ICMESA was going about its usual business of producing chemicals when one of its reactors released a toxic cloud. The cloud contained roughly 6,600 lbs of chemicals, blew 164 feet into the sky and dispersed into surrounding communities, according to this Japan Times article. Among other chemicals, the cloud released TCDD, a dioxin associated Agent Orange and Victor Yushchenko’s poisoning, into the air.

The mass poisoning that followed started with children, who noticed lesions on their skin. Chloracne, the dioxin-related skin disfiguration that Yushchenko is known for, also began appearing on peoples’ faces.

When authorities finally began investigating the accident five days later, rabbits were dying in large numbers. About 4% of local farm animals died, and 80,000 more were killed to halt contamination, according to the Japan Times.

For years after the event, people in the Seveso region experienced hormone disruption (an unusually high number of female babies was born during that time), neurological disorders, cancer, and immune disorders.

As a result of Seveso, Europe introduced new industrial safety legislation.

The Sandoz Spill

Image: rbrands/Flickr

How does a tiny fire in a pharmaceutical company’s production plant storage room lead to toxic waste being released into the Rhine River? Perhaps the answer to that question lies more closely in who the big pharma company is.

Sandoz Laboratories created the hallucinogenic LSD, then marketed it under the name Delysid from 1947 to the mid 1960s. Bearing that in mind makes it easier to see how a storage room could lead to toxic waste being released into Germany’s Rhine River. In 1986, a storage room fire helped release 30 tons of herbicides, pesticides and mercury into the Rhine, killing many of the fish and contaminating water supplies along the river.

In 1996, Sandoz merged with Ciba-Geigy to become Novartis, which today is known for refusing to give free flu vaccines to people in developing countries and losing a $250 million sexual discrimination suite. Ouch.