When one of the knights of the Round Table sallies forth to free a damsel in distress, he does not just free her. Her villainous captor is often some sort of local baronial lord who has taken to imprisoning, raping, killing, and occasionally even eating the peasants who work the land near the castle. Thus, defeating the monstrous lord and rescuing the damsel also means, for our heroic knight-errant, protecting the beleaguered peasants.

David Heinemeier Hansson, the creator of Ruby on Rails and CTO of the tech company Basecamp, brought this image to my mind in a recent discussion about tech monopolies, held virtually by the American Economic Liberties Project.

“We live on their lands,” Hansson said about the tech monopolies.

“It is a very uncertain place to live.”

It is incredibly frightening, he said, to know that “our business can disappear essentially from one day to the next if these kings of the digital platforms decide—out of spite, out of negligence, out of any of the other impulses they might have—to do what they do. And then we end up, as business people, as creators, feeling like there is just nothing we can do.”

Is a rescuer on the way?

Last week, on October 20, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google, alleging that the search giant is illegally protecting its search monopoly.

Google Conquered the Territory

It is worth bearing in mind that the defendant in the federal lawsuit is Google LLC, the search-focused subsidiary of its parent company Alphabet, Inc., (the fifth largest company in the world, as measured by market cap). The lawsuit, thus, is focused exclusively on Google search and search advertising—it does not touch directly on any of the many other ventures Alphabet is involved with.

So what does this lawsuit mean for internet search?

As everyone in the SEO world (Search Engine Optimization–the practice of building and promoting websites so they appear high up in internet searches) knows, “search” really just means Google. Why?

Because, as the lawsuit notes, “Google in recent years has accounted for nearly 90 percent of all general-search-engine queries in the United States, and almost 95 percent of queries on mobile devices.”

SEO strategists, and really anyone who relies on traffic from Google for their business, has experienced something like Hansson describes in terms of living on the Google lord’s lands.

Matt Berman is the President of Emerald Digital, a full-service digital marketing agency in New York City and New Orleans.

“Right now, we take Google as gospel,” he told me.

“We code our websites specifically for their crawlers. We write our copy the way they like it. We write our ads to their specification.”

And at least in part because of that enforced dependence, SEO and other digital marketing professionals have an uneasy relationship with Google.

“As a niche SEO service provider, I’m surrounded by a community which itself has immense mistrust in Google,” my friend Greg Heilers, one of the owners of the SEO firm Jolly, told me.

Heilers also identifies with Hansson’s comments.

“Anyone running a search-dependent business wakes up and goes to sleep monitoring Google’s moves—that is, unless they’re an old hand and know their nerves are better served keeping a ~72-hour news cycle approach versus daily,” he said.

“In this context, it’s easy to see how Google’s dominance makes it just as or even more impactful than the greater economy.”

How Google Did It

How did Google get so dominant that the company name is now synonymous with “search”? That they have innovated and created a great product is not in dispute. But does Google account for 95 percent of mobile internet searches sheerly through excellence—or have they broken the rules to get there?

“It’s true that other search engines like DuckDuckGo exist,” Heilers said.

“What’s more, the downfall of greats like Yahoo are well known to be more market awareness failures than malfeasance on Google’s part.”

And Google itself, as you might imagine, is not pleased with the suit. They deny they have broken the law. Kent Walker, SVP of Global Affairs, warned in the company’s official response to the lawsuit that the suit would “artificially prop up lower-quality search alternatives, raise phone prices, and make it harder for people to get the search services they want to use.”

As Walker wrote on October 20:

“Today’s lawsuit by the Department of Justice is deeply flawed. People use Google because they choose to, not because they’re forced to, or because they can’t find alternatives.”

But to my eyes, Walker’s response resembles the pumpkin patch hay ride where I take my daughter every year. You set up a few straw men around the perimeter of the pumpkin patch, and then drive around in the back of a tractor and pummel them with miniature pumpkins.

Nowhere in the complaint does the DOJ claim that people are “forced” to use Google, or allege that no one knows how to find alternatives. But, armed with diagrams and GIFs, those are the “claims” Walker spends the rest of his response pummelling.

But that is not what the lawsuit says at all. It alleges that Google uses a combination of carrots (like revenue-sharing) and sticks (exclusivity contracts) to force manufacturers and developers to always make Google the default choice anytime a desktop or mobile user searches the internet.

The Mobile Search Trap

One of the most shrewd ways Google pulled this off is the two-step “trap” they built for mobile manufacturers and developers, which the lawsuit explains in detail. Unlike Apple’s “closed ecosystem,” Google made their Android operating system open-source, which was a boon for developers who could easily modify operating systems based on the Android source code. As the complaint points out, “developing an operating system from scratch is extremely expensive.”

But there is no such thing as a free lunch. The open-source character of Android was the first piece of cheese in the “trap,” which enticed developers to build Android-specific applications and encouraged manufacturers and carriers to adopt the Android operating system.

It felt relatively risk-free:

“An open-source model suggested that they [mobile phone manufacturers and carriers]—and not Google—would ultimately retain control over their devices and the app ecosystem on those devices,” the lawsuit says.

But as more carriers and manufacturers adopted Android, more developers built apps for Android, which consumers enjoyed, thereby enticing consumers to purchase more Android devices. This, in a self-reinforcing cycle, incentivized more carriers and manufacturers to adopt Android, thus more apps, more customers, and on ad infinitum.

The second piece of cheese in the trap was… cheese, i.e., cash.

“To help the Android ecosystem achieve critical mass and to advance the network effects, Google ‘shared’ its search advertising and app store revenues with distributors as further inducement to give up control,” says the complaint.

But Google had sticks in its arsenal as well—not just carrots. The sticks, used to make Google search the default option at every “search access point” (e.g. Chrome, Google search app, Google search widget, Google Assistant), were exclusionary agreements that manufacturers and carriers had to sign in order to get access to the Android apps that consumers loved, and in order to keep getting the search advertising revenue-share. So in this way, the carrots turned into the sticks.

Is Google Breaking the Law?

Their strategy was undoubtedly shrewd, even conniving, but being smart is not illegal. So why is the DOJ suing Google? What are they supposedly guilty of?

The DOJ lawsuit is brought under Section 2 of the Sherman Act, an anti-monopoly law originally passed in 1890. Section 2 is designed to protect the market from companies that possess monopoly power and use it to squeeze out their competitors.

“The fact that a company possesses and abuses a high degree of market power warrants antitrust scrutiny under Section 2,” explains the American Economic Liberties Project.

“A U.S. monopolization case against Google is long overdue. The sheer number of markets Google dominates—mobile operating systems, general search, online video, mapping, email, display advertising, and browsers—gives Google unprecedented power over online commerce.”

And as we have seen above, the use of carrots and sticks (and carrots turned into sticks) certainly appears to be an abuse. And SEOs and other marketers have felt the ill effects of Google’s power firsthand.

Negative SEO Effects

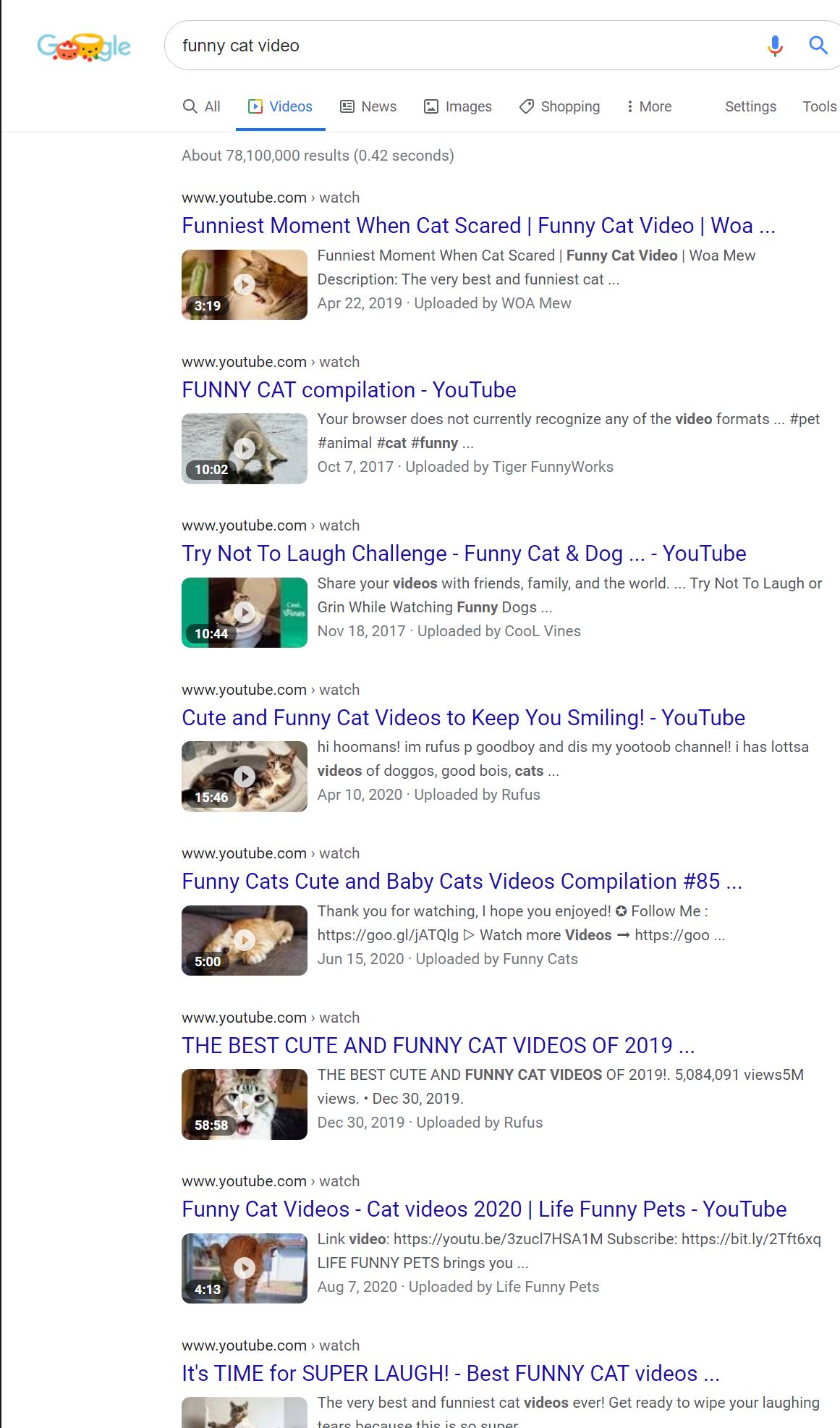

One is the gradual cluttering of the SERPs (Search Engine Results Pages–the list of results that pops up whenever you Google something). While Google SERPs used to be the gateway to the internet, they have gradually become billboards for Google itself. How so?

One is the placement of paid ads above the organic results.

“The number of ads keeps increasing,” Stephen Roe, founder and head of digital strategy at Thoughtful Prose, said.

“It’s currently at four, which harms the user experience.” But it is not just ads.

“Google mines data from websites for featured content, displaying them without permission and driving down clicks,” Roe said.

The various kinds of “featured content,” like snippets that directly answer your question, “People also ask” boxes, Knowledge panels with Wikipedia summaries–all of these pull content from third-party sites and display them directly on the SERP.

These are sometimes helpful for users–they reduce the amount of clicking and scrolling you have to do to get the answer you want–but they really just constitute Google ripping other people’s sites off and taking the information for themselves, which prevents the owners of these third-party sites from getting the traffic and engagement that their own content has earned.

Of course, Google has its own content too, like YouTube. Notice that when you search for a video, Google almost exclusively returns YouTube results (despite the existence of many, many video hosting sites).

Between featured content displayed directly on the SERP and Google web properties getting pride of place on the SERP, fewer than half (42 percent) of Google searches lead to someone clicking organically onto a third-party site not owned by Google.

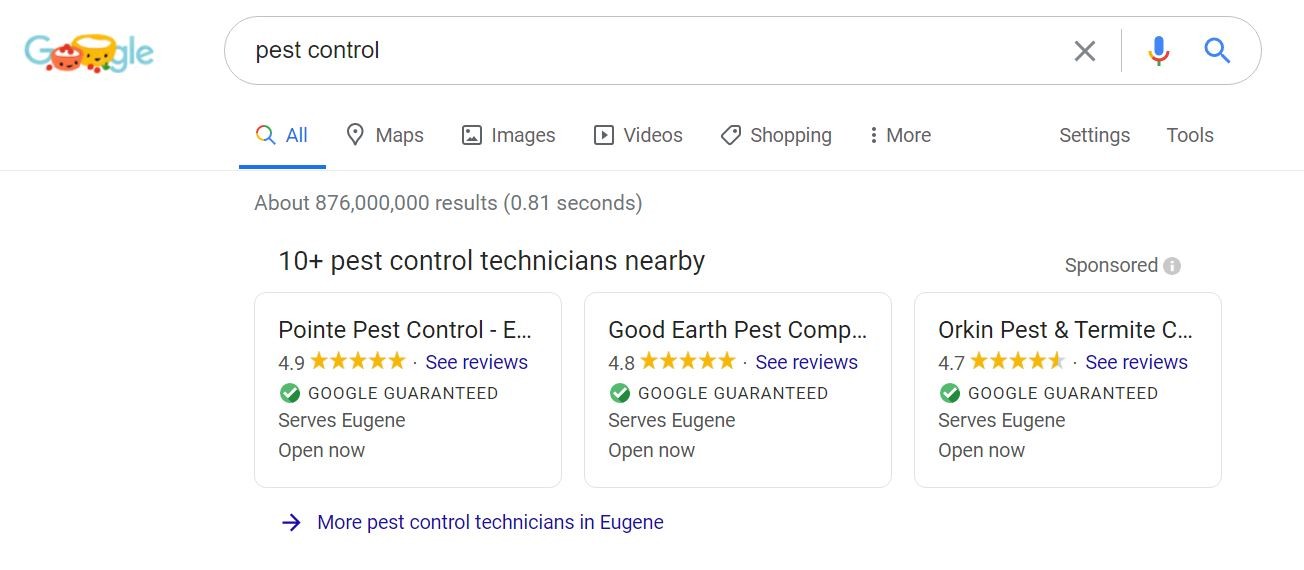

Experts in “local SEO,” i.e. SEO for locally-focused searches like “gardener near me,” have also been watching Google take over the top of the SERP with ‘Google Guaranteed’ local results which route the entire customer acquisition process through Google.

As third-party site owners see ever-declining traffic from the only meaningful search engine in town, they have Featured Content, Google AdWords, Google Guaranteed Results, and Google awarding pole position to its own properties to thank.

And even business owners and marketers who pay for ad space on Google worry that the tech giant is taking advantage of them.

“We have noticed that Google’s cost per click on search ads has risen substantially for terms that don’t even have other advertisers bidding on them,” Max DesMarais said. DesMarais is a digital marketing strategist with Vital Design and also the owner of his own website, hikingandfishing.com.

“A big example is with our client’s brand names, where no other ads are showing up, yet our own client has to pay multiple dollars for one click on their own, non-competitive brand name.”

In Google’s Defense

But not everyone is convinced that any of this constitutes an anti-competitive abuse. John Tamny, editor of RealClearMarkets and Director of the Center for Economic Freedom at FreedomWorks, criticized the lawsuit in Forbes.

Noting that MySpace had more traffic than Google back in 2006, that Microsoft’s Internet Explorer got beat out by Firefox and Chrome, and that upstart Zoom (IPO’d in 2019) has overtaken GoToMeeting and Google Meet as the videoconferencing software of choice for locked-down remote workers, he wrote, “that dominance in the technology space” is “ephemeral.”

Further, Tamny argues that Google’s incredible market power actually ensures it will be disrupted–like moths to a flame, VCs and entrepreneurs are attracted to industries with companies that have monstrous valuations, ensuring that competition is always around the corner.

But Tamny’s argument takes a weird turn:

“It’s apparent that Google’s long-term dominance is only apparent to a Department of Justice that is only capable of seeing the present. Think about it. Google surely doesn’t see its market power as endless. If it did, why would it pay Apple for prominent real estate on its products?”

If you are confused, join the club. Tamny’s article is supposed to be about why the Google lawsuit is stupid. But instead he proves that Google needs to be sued! He’s making the Justice Department’s argument for them.

Google’s market power is not actually endless, as Tamny correctly points out. Someone with a better business and better product very well could disrupt them. Google knows this, and that is exactly why it pays $8 billion to $12 billion to Apple every year–to artificially preserve its market power!

That is, after all, precisely what the lawsuit alleges:

“Apple’s RSA incentivizes Apple to push more and more search traffic to Google and accommodate Google’s strategy of denying scale to rivals. For example, in 2018, Apple’s and Google’s CEOs met to discuss how the companies could work together to drive search revenue growth. After the 2018 meeting, a senior Apple employee wrote to a Google counterpart: ‘Our vision is that we work as if we are one company.’”

What’s it called when multiple companies conspire to freeze out competitors and raise their profits? Sounds an awful lot like a cartel to me.

But I spoke to a few SEOs who nevertheless think the lawsuit is unnecessary.

“The methods mentioned in the suit seem to be standard business practices aimed at improving their product and keeping their market share,” John McGhee, Managing Partner of Webconsuls LLC, said.

“The vast majority of Google’s information is user-generated, Google Ads is an auction based system so prices are user generated, and people can easily switch their search engine. Essentially Google is a monopoly because we the people made it that way.”

On Twitter, Mark Cuban also came to Google’s defense with a similar argument. A back-and-forth with anti-monopoly scholar and activist Matt Stoller of the AELP followed.

Cuban downplayed the importance of paying for default settings. Stoller, however, replied with the same point that somebody needs to tell Tamny: “If defaults have no value and the product is just better, then Google is pissing away $11B a year for no reason. If defaults have value there’s market power at work.”

In other words, Google sees the default position as valuable. So valuable, in fact, that they are willing to pay Apple a sizable chunk of their profits in order to lock down that default position. According to the lawsuit, those ad revenue-sharing payments from Google “make up approximately 15-20 perent of Apple’s worldwide net income.”

Cuban, however, compared paying to make a search engine default with paying for advertising.

In reply, Stoller said, “Australian and British competition authorities both found defaults are a meaningful barrier to entry and consumer switching is relatively limited. They also are defensive, a way of excluding consumers from trying other products.”

So is making Google search, Google Chrome, and other Google search access points the default merely advertising? Or is it anti-competitive behavior? McGhee says it “is no different than paying for shelf positioning in grocery stores.”

But Jameson Zimmer, a strategist at Centerfield Media Holdings, disagrees with this assessment.

“I’m often struck at how relatively unsophisticated the average consumer that hits one of my sites is. A huge percent of them, if they engage with chat or contact, can’t even tell the difference between a third party site like e.g. Wirecutter [a product review site owned by The New York Times] and the product/company they Googled,” Zimmer said.

“The expectation seems to be, ‘If I type {product} into Google, I will land on the {product} website.’ This, to me, really supports the case that ‘defaults matter’ as indicated by the US case — for all intents and purposes, for the average user, Google is the internet.”

Future Outlook for the Lawsuit

Now for the multi-billion dollar question: What will happen next? Can the Justice Department win the case? And even if they do win, what will it change for SEO and for the average internet search experience?

“Most antitrust cases settle or dismiss before trial,” the AELP notes. But Hansson, toiling away on Lord Google’s lands, hopes that the case will not end in a settlement.

“The most important thing for me is to hope that this doesn’t just turn out to be a lame fine,” he said at the AELP event last week.

“That’s the worst thing that could possibly come out of this.”

Why? At that event, Commissioner Rohit Chopra of the Federal Trade Commission explained that settlements actually incentivize rulebreaking. Granting total immunity to executives and foregoing a stipulation to change behavior ensures that nothing ever gets better.

“A settlement with a fine and some paperwork is not going to fix the problem,” Chopra said.

“It is only going to incentivize bad behavior going forward.” If a company can act unethically—even illegally—and only have to pay a fine, then it will just factor the fine into the cost of doing business. If you want to get ahead, then you just have to pay for it, and the economic benefit of cheating will end up far outweighing the cost.

What the SEO Community Thinks

The SEOs I spoke with envisioned a variety of outcomes. Berman, of Emerald Digital, imagines a Google break-up having somewhat mixed results.

“If I see an ad about polo, it’s just an interruption. If I see an ad about guitar pedals, I’m immediately interested. Google has used its monopoly position to gather this data,” he said.

“Their data collection extends to users who use their search products, GMail, Android, location services, maps, and more. Breaking up Google would mean their data collection efforts would suffer. This is great for users, but bad for advertisers.”

Jake Meador, director of content strategy at Mobile Text Alerts, sees a bigger regulatory—even philosophical—problem.

“I do have concerns about monopoly-equivalent power with Google,” he said. But he does not think that this lawsuit gets to the core issue, a sentiment widely shared among the SEOs that I spoke with.

“My fear with the current proposals is that we don’t really have the conceptual framework we need for regulating a company like Google. Google is too powerful, but it’s hard to demonstrate a true monopoly because it is not difficult for someone to use another search engine.”

This is the central issue. Google’s presence feels monopolistic, but in the digital space another option is only a click or two away, in many cases.

“The challenge for regulators is how to think about regulating companies that are both too powerful and freely chosen by most of their users. I think it’s a problem we need to solve, because if we don’t this nation is going to belong to a very small syndicate of tech companies in the near future.”

For his part, Zimmer, from Centerfield, doubts it will have much of an effect on users.

“I simultaneously believe that Google’s use of exclusive contracts is anticompetitive, but that ‘breaking them up’ at the carrier integration level is unlikely to change consumer preference for Google products,” he said.

Zimmer believes that search competition is more likely to come from the personal assistant space.

“Amazon’s Alexa is probably the best example of what ‘disruption’ looks like for a product like Google search.” Why?

“It’s a total re-think of the search experience combined with a tech breakthrough, which I think is the most likely thing to eventually break off more parts of Google’s search dominance.”

Roe, of Thoughtful Prose, would be interested in seeing a structural solution, “in much the same way as Big Oil back in the day. Perhaps with Gmail, Search, YouTube, and other properties divided up.”

This hearkens back to the most recent major Section 2 litigation under the Sherman Act (all the way back in 1998). As the AELP writes:

“The judge who presided over the Microsoft case rightly proposed a structural remedy to split Microsoft up into two companies. But this remedy was overturned on appeal, and the Bush administration quickly agreed to settle the case. The settlement was inadequate, requiring only that Microsoft share certain programming information with third-party companies.”

Nevertheless, the overall effect of the litigation chastened Microsoft because it got worried about potential anti-monopoly action in the future.

It is precisely this history that makes Michael Heiligenstein, director of content strategy at Flex, so bullish on the DOJ litigation.

“Google has, for the past 20 years, been living in an environment free from any kind of governmental pressure,” he said.

“Now that they do have regulation, it’s going to change the way they behave.”

Nobody knows what will happen next, how long the suit will take to wind its way through the courts, or if the parties will pursue a settlement.

“The anti-trust suit will likely take years, and it’s hard to say where it will end up,” Heligenstein said. But that does not mean we will have to wait years to see any results.

“As long as it’s open, it will change how Google operates; when Microsoft faced a similar suit in the late 90s, they became much less aggressive. Because of this pressure, they even decided not to crush a small, up-and-coming tech company: Google.”