For years the resiliency in America’s infrastructure has been a bipartisan concern. In recent weeks, reasons for extending this concern to food infrastructure have loomed increasingly larger. The closing of some of the nation’s largest meat processing plants, and subsequent reopening upon President Trump’s classification of meat processing plants as “essential infrastructure” provide legal clout to this notion.

While the designation of meat processing plants as essential infrastructure is a stop gap measure of importance, a growing number of smaller meat producers are excluded from being part of a resilient food system solution. Years of consolidation of regulatory focus on the largest of meat producers have left untenable burdens on smaller meat processing plants (meat processing plants handling less than 10,000 cattle head a year). In a time at which smaller farms and meat processing plants can play a particularly crucial role at mitigating national food supply chain issues, it’s extremely important that these smaller players are legally factored into whatever food infrastructure bill is passed.

The Processing Revival and Intrastate Meat Exemption Act or the PRIME Act — re-brought before the house by Representative Thomas Massie (R-KY) and Representative Chellie Pingree (D-ME) — seeks to lower the regulatory burden on local meat processing plants. While quality control of our foods is important, historical clout of the largest corporate farms and meat processing plants have created a regulatory system that only works for the largest of meat-making entities and harms American farmers, American consumers, rural economies, and public health.

In our view the PRIME Act is crucial to support a more resilient and antifragile food supply in America.

Some of the issues with current regulations on local meat producers and processors the the PRIME Act would remedy include:

Laws written with large processing companies in mind make it unrealistically hard for small plants to comply due to scale and cost.

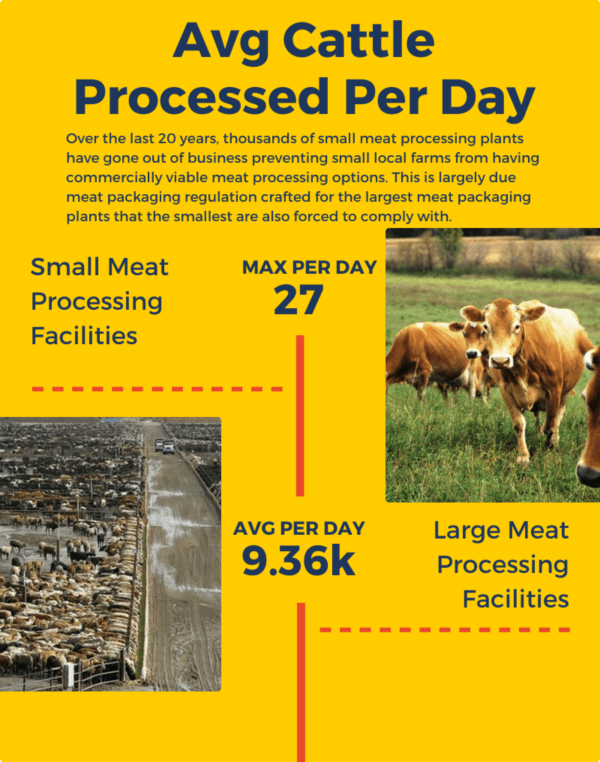

Thousands of local small meat processing plants have closed within the last 20 years due to regulations meant for the largest meat processing facilities. Small federally-inspected meat processing plants are capped at plants that process less than 10,000 heads of cattle a year. Note that that’s the upper limit of small meat processing plants with many custom slaughter houses processing many fewer animals. By comparison, to qualify for processing at many of the nation’s largest meat processing plants, a corporate farm (such as Tyson or Purdue) would need to be able to field a processing order on the scale of 300-400 cattle head per hour, 1000 hog head per hour, or 170 chickens per minute. These larger meat packaging facilities often do not field on-off meat processing orders from smaller farms.

Effectively, no local or family farms produce meat on this scale nor need to process this volume of meat. While safety regulations at the largest plants in the nation are important, the need for the same safety systems at local processing plants that may only process a maximum of 1/1000th of the number of animals is dubious and cost prohibitive.

Many economic stakeholders suffer when disadvantages of scale for small meat packing plants are exacerbated by regulatory costs.

Many local meat packaging plants put as much as 6-10x as much labor into each pound of processed meat when compared to the largest meat processing plants. By asking these smaller plants to additionally perform upgrades to equipment, testing, or processes similarly to the largest plants, the cost per pound of local meat rises dramatically.

These labor cost issues mean additional costs are passed to local farmers to process their food. When farmers have trouble passing some of these costs to the consumer (who oftentimes is comparing local meat prices to meat prices in big box stores), local meat processing plants lose customers and local farms have no effective route to sell their product.

State-inspected meat processing facilities are required to fulfill the same requirements federally-inspected meat processing facilities are.

With federally-inspected processing standards aligned with the needs of the largest meat processing plants, this effectively places undue burden on local meat packing plants. This centralization of meat processing options excludes states from inspecting meat in ways that are realistic for the needs of their local farmers and consumers.

What is needed is for state inspections to be able to perform higher quality inspections than those performed at the federal level. And this means looking at the unique regulatory needs of both consumers and local farmers within each state.

Undue burdens on local meat processing plants have led to lack of access to USDA-approved meat processing plants for small farmers in most states.

With so few smaller meat processing plants able to meet the regulatory burden needed to be able to claim “USDA approval,” many states only have one or less options for USDA approved processing of local meat.

At present date, there are over 6,000 meat packaging plants regulated by the USDA (or more precisely the FSIS) in America. Of these, only 263 meat packaging plants are in the smallest category by volume slaughtered.

For example, there is only one USDA inspected chicken slaughter facility available for small farms in the state of Tennessee. Many states have none, or single digit numbers of facilities that may be hundreds of miles away from farms.

This is a major hindrance to the availability of local and small farm meat, as meat is required to pass through a USDA approved facility in order to be sold across state lines or in groceries.

While local farmers can process meat via “custom exemptions” (small non-USDA approved slaughter houses) this means the meat must be consumed by the owner of the meat and may not be sold part-by-part as is commonly done in groceries and to restaurants.

While some enterprising farmers have decided to build their own USDA-approved processing sites, this process typically costs millions of dollars, and has no guarantee of gaining approval.

The requirement that meat processed at local custom slaughter facilities be consumed by the current owner of the animal effectively excludes many individuals from purchasing local meat.

Under present regulations meat farms can sell live animals to customers who may then take the animal to a “custom slaughter” shop for butchering. But neither the meat farm nor the customer may then sell the processed meat in a piece-by-piece fashion (other than selling in whole, half, or quarter carcass denominations).

This undue burden means that individuals who do not have the funds to buy local meat in very large volumes, or individuals who don’t have freezer storage space for potentially hundreds of pounds of meat effectively cannot buy local meat. This excludes many individuals who are local to farms (primarily rural residents who are likelier to live extended distances from food sources). Additionally, in many cases this excludes local meat from being sold at grocery stores, restaurants, and other local food establishments.

Our Vision For a More Resilient Food Supply

Food infrastructure — as an idea that supports sustainability and resiliency in food systems — involves the development of roads, storage buildings, processing plants, shipping facilities, and rail yards for the sake of food consumption, waste management, retailing, distribution, storage, processing, and production. It has shown that focus on these elements as well as supportive regulatory frameworks for both small and large food manufacturers helps to create resilient food systems.

The PRIME Act helps to support food infrastructure which is currently failing to uphold robust supply chains during the Covid-19 crisis. The PRIME act would primarily do this through allowing smaller meat processing plants (those that process less than 10,000 head of cattle a year), to distribute their meat within that state (or other state’s with corresponding standards) through state-inspection of meat packaging plants.

This would mean that USDA standards currently required to be met at state levels, and which put unrealistic expectations on small meat packaging plants, would no longer need to be consulted for smaller meat processing plants.

If passed in a form that deals with many of the issues detailed in this editorial above, the PRIME act would serve as a massive boon to local economies, farmers, consumers, and help to right a flawed consolidation of food infrastructure around only the largest food providers in recent years.

Below we’ve detailed some of the reasons why the PRIME act would support a more resilient and antifragile food supply in America. Additionally, we’ve noted some areas in which the PRIME act may not go far enough and additional changes to the framework that we seek.

Benefits of the PRIME Act

- Help establish infrastructure in rural communities

- Improve Farmers’ incomes and opportunities

- Increase consumers’ access to locally raised meats

- Locally raised meats are often of higher quality than those of national brands who often use deceptive labelling practices to claim “made in America,” “organic,” “grass fed” and other related labels.

- Reduce stress on animals from long distance hauling

- Reduce transportation miles and greenhouse gas emissions associated with long distance hauling

- Create jobs in rural communities

- Support resiliency and redundancy in critical food supply chains

- Utilize

Additional Legal Changes That May Be Needed

- Support and legal framework for regional networks of farmers so that they can pool resources and become part of the supply chain of large retailers

- Financial incentivization of small meat processing plants that are necessary but do not benefit from the economy of scale the largest meat processing plants achieve

- The employment of rural veterinarians and veterinary technicians to conduct inspections at local plants in a cost and resource effective manner (could be achieved under the Talmadge-Aiken Act)

- Additional protections for small farms and meat packaging plants in America or regulation of monopolistic and very large corporate farms and packaging plants. Measures such as those laid out in Senator Cory Booker’s Farm System Reform Act of 2019. This act seeks to stop the formation of new concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). CAFOs are presently defined as farms having more than 82,000 laying hens, 125,000 chickens, 2,500 pigs, 700 dairy cows, or 1,000 cattle. As well as changes country-of-origin labelling practices for meat that are abused by the largest farms. Rationale for this act include the proliferation of antibiotic resistance due to meat created by the largest factory farms, the burden of waste management, the damage created to rural economies, and support for small family-run farms.

If you feel so moved as to advocate for the PRIME Act, know that this legislation is still being formed and is now being introduced by Reps. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) and Chellie Pingree (D-Maine) and Senators Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Angus King (I-Maine). Contact your local congressional members to urge them to cosponsor the PRIME Act today.

Additional Sources:

http://tbfoodstrategy.com/pillars/food-infrastructure/

https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/22/business/tyson-pork-plant-iowa-coronavirus/index.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/28/trump-meat-plants-dpa/

https://www.aamp.com/news/documents/LossofSmallSlaughterhouses.pdf